The argument in the video was simple.

Two fictional students, Andy and Anna, both go to a public school — but Andy’s school receives less state funding because it is a charter school. The ad from the Indiana Student Funding Alliance prompted viewers to ask: Shouldn’t Indiana lawmakers close this unfair funding gap between charters and traditional public schools?

The message reached voters throughout Indiana just as state lawmakers convened for this year’s legislative session. The roughly $500,000 ad campaign was the latest in a years-long push to direct more state and local funding to charters with the help of the alliance, an influential group of charter backers and nonprofits.

As the session began, charter schools and their backers had particularly pressing reasons to step up their lobbying and marketing efforts. Indianapolis Public Schools, the state’s largest district, planned on seeking roughly $413 million in new property taxes through a 2023 ballot measure. And charter schools were frustrated with the prospect of getting a relatively small slice of that money; some charters wouldn’t get any of it. Additionally, property values in general were rising, sending extra funding to some local school districts but not to charters.

Although the alliance had existed informally for a few years, last year its members organized the group under a formal name. It got support for its marketing campaign from groups like the Hoosiers for Quality Education nonprofit — which also has a political action committee that has donated nearly $1 million to lawmakers in the last three years alone and supports school choice of various kinds.

The Indiana Student Funding Alliance’s campaign paid off. After lawmakers enacted several changes this year, charter schools scored one of their biggest wins since they started in Indiana over 20 years ago: a modified state funding system that gives them more money. The changes, combined with a nearly universal voucher system lawmakers passed this year, mark a critical milestone for an Indiana education landscape that favors school choice now more than ever.

Education interest groups and PACs have long lobbied state lawmakers and tried to sway public opinion. The Indiana Political Action Committee for Education, for example, is the political arm of the Indiana State Teachers Association that consistently gives money to lawmakers’ campaigns.

But the changes this year represent a critical juncture for school funding in Indiana. In addition to increasing the state’s per-student charter funding, school districts in Marion County and three other counties now must not only share referendum funds for operating expenses with charters, but also future property tax increases as well.

Even with the Republican supermajority’s strong support for school choice in general, it was important for advocates like the Indiana Student Funding Alliance to highlight charter schools’ funding challenges, said Scott Bess, the executive director of Purdue Polytechnic High School, an Indianapolis charter that is part of the alliance. The group had existed loosely for years, he noted, but the IPS referendum — and charters’ inability in general to tap local property tax revenue — elicited a more organized response.

“Those two things happening at the same time really sent home the message that if we don’t do something and do something more aggressively, these gaps are going to get to a point where it’s not financially sustainable,” Bess said.

Rep. Ed Delaney, a Democrat on the House education committee who has consistently opposed charter schools and vouchers, sees lobbying by the alliance and similar efforts as the work of an “education industrial complex.”

“I think they’ve reached a point of excessive power,” he said. “And what comes with that is greed and a lack of judgment.”

Charter school backers turn to Facebook ads

How these changes will affect traditional public schools’ budgets is unknown, given fluctuating property values among other factors.

The Mind Trust, a powerful Indianapolis nonprofit that advocates for charter-friendly policies and which joined the Indiana Student Funding Alliance, estimates those changes will ultimately provide an additional $2,259 per student for charter schools within IPS.

Members of the alliance are celebrating these changes as wins.

The alliance is made up of partners such as the Indiana Charter School Network and the Walton Education Coalition, an education advocacy group, said Betsy Wiley, president of the Hoosiers for Quality Education nonprofit that helped fund the alliance’s campaign. (The Walton Family Foundation, which is legally separate from the Walton Education Coalition, is a funder of Chalkbeat.)

Hoosiers for Quality Education also has a political action committee that has received funding from wealthy donors and groups frequently associated with education reform efforts such as charter schools and vouchers.

Together, the Hoosiers for Quality Education nonprofit and the related Institute for Quality Education nonprofit — which distributes private school tuition support as a scholarship granting organization — paid for at least $49,000 in Facebook ads, such as the one featuring Andy and Anna that promoted more funding for charters, according to Facebook’s Ad Library. Those ads ran from September 2022 to the end of the session in April.

“This year was different in that a group of folks who strongly believe that public charter school students deserve the same funding as their traditional district student peers came together in a more coordinated fashion,” Wiley said in an email.

Rep. Bob Behning, the Indianapolis Republican who was chairman of the House education committee in the 2023 session, had previously pushed for school districts to share referendum revenues with charters. But this year, he said, the IPS referendum elevated the issue’s importance in his mind. (IPS ultimately nixed its plan to put the referendum on the May primary ballot, although the district may revive the proposal in some form.)

The advertisements by charter backers indicated a general motivation to push for “some level of parity” for charter school funding, he said.

Lawmakers did also approve a $312 million increase for traditional public schools right before the end of this year’s legislative session. But critics such as Delaney argue the push to increase funding for charters is just part of a bigger agenda to dismantle the traditional public school system.

“The fundamental truth is they are not interested in traditional public education,” he said. “They do not support it, they do not believe in it, but they don’t have the courage to stand up and say” that traditional public schools should close.

What increased funding means to charters

Anna and Andy used in the Indiana Student Funding Alliance ads may be fictional, but Dwayne Sullivan and his mother, Susan Sargeant, are very much real.

Dwayne is in the first class due to graduate next year from the Rooted School, an Indianapolis charter school with grades 7-12 that opened in 2020.

Even though her son will graduate soon, Sargeant is hopeful the additional funding enabled by the changes to state law will support higher teacher salaries to attract high-quality teachers to Rooted.

“That’s a big, big, big deal, especially for a charter school that’s starting out,” she said.

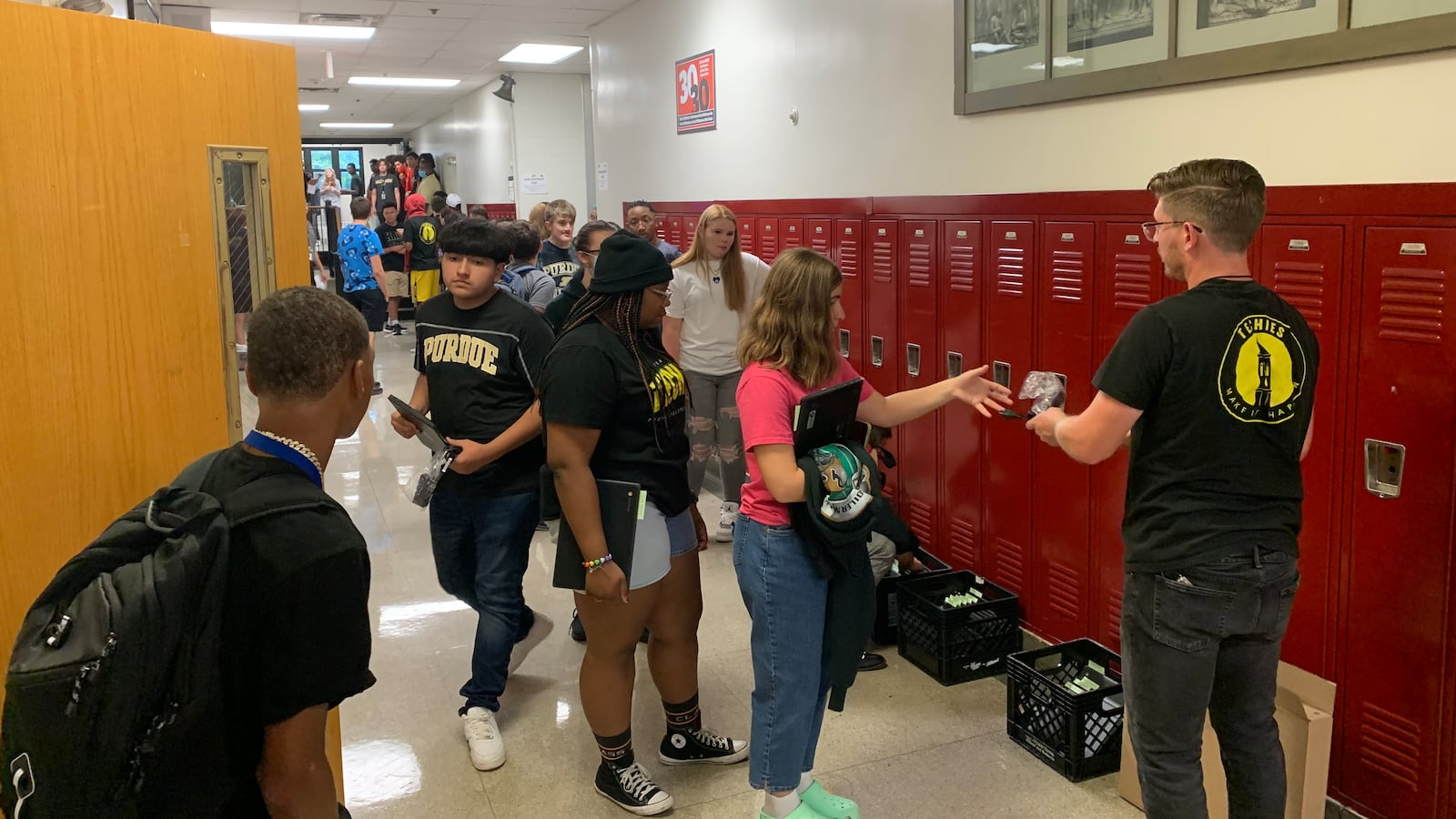

At Purdue Polytechnic High School, which has two campuses in Indianapolis, extra operating revenue will also help cover the cost of materials needed for the experiential learning that the school emphasizes through robotics, woodshop, and even a coffee shop that students recently opened at the Englewood campus of Broad Ripple High School.

Both charter school and traditional public school advocates see the referendum sharing requirement as an opportunity to collaborate to convince voters to pass future property tax increases for schools.

Still, some school district officials are worried about the net effect of sharing incremental property tax revenues with charters.

Rafi Nolan-Abrahamian, chief of staff for South Bend Community Schools, said the district is grateful for the $2.1 million in additional yearly revenue it’s getting due to the last-minute change made by lawmakers. And he said each funding change favoring charters on its own is probably manageable.

“But we are concerned in particular about the precedent that some of these are setting, and the sort of underlying motivations and rationales behind them,” he said.

Meanwhile, pro-charter groups are stressing that this year’s policy changes don’t meet all their long-term goals.

“Our goal remains the same, the same that it’s been for many, many years, which is parity in funding for public charter school students,” Wiley said. “And we’re not there yet.”

Amelia Pak-Harvey covers Indianapolis and Marion County schools for Chalkbeat Indiana. Contact Amelia at apak-harvey@chalkbeat.org.