Sign up for Chalkbeat Indiana’s free daily newsletter to keep up with Indianapolis Public Schools and statewide education news.

For years, a small district of 1,100 students just east of Indianapolis aimed to ditch the fees that had created barriers for students and burdens for their families.

But officials at Charles A. Beard Memorial schools knew if they took on the costs, they’d have to sustain them long term, said Superintendent Jediah Behny. So they started small — first eliminating entrance fees for students to school sports events — before eventually dropping the fees for textbooks and materials in 2020.

“We wanted to eliminate the likelihood that some kids were getting something that others weren’t,” Behny said.

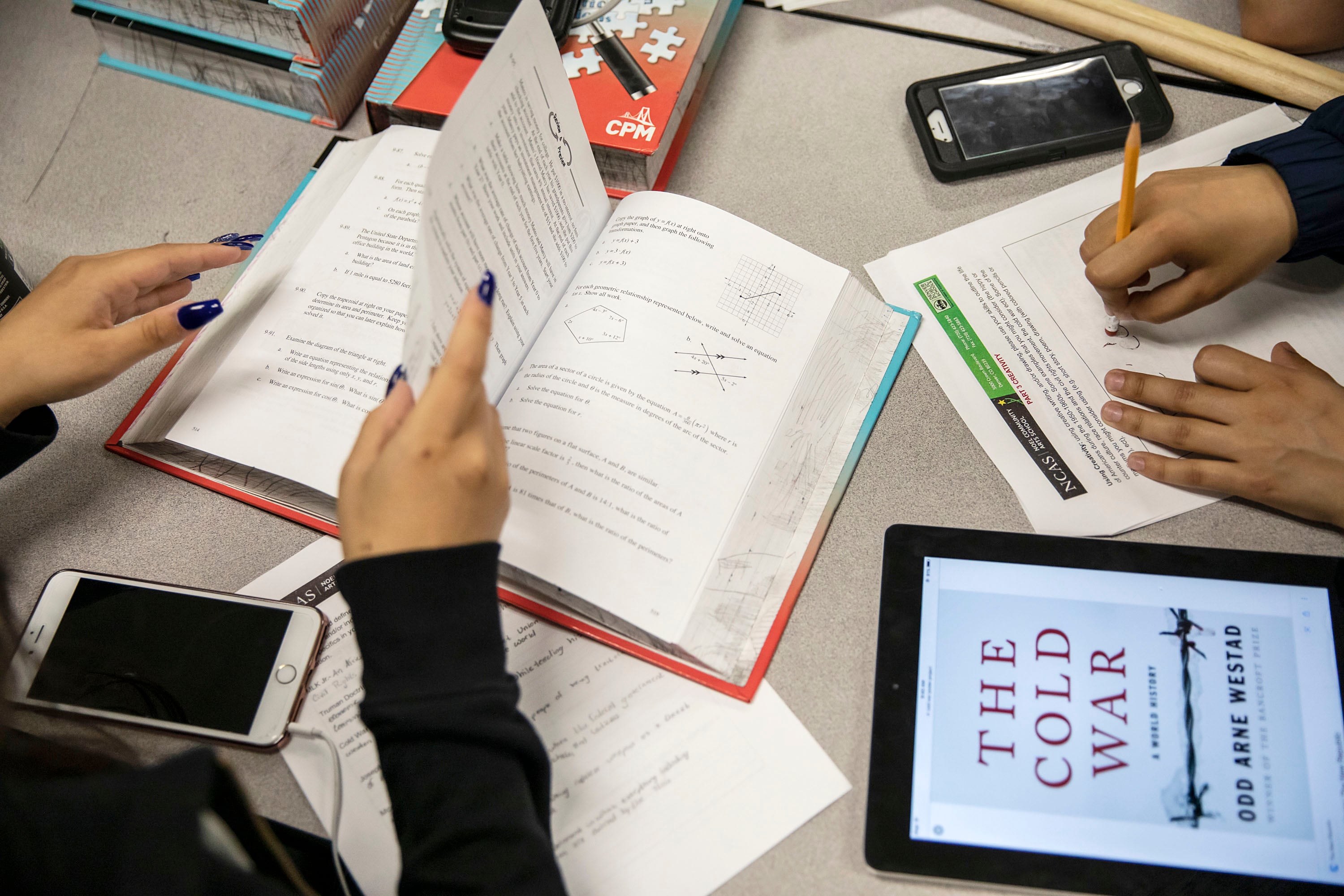

Beginning this school year, after a law passed in the 2023 legislative session, all Indiana schools will be required to follow the district’s example and stop charging families for curricular materials, including textbooks, iPads, and Chromebooks.

The change, championed by Gov. Eric Holcomb, is meant to lighten the load on Hoosier families, who reported paying hundreds of dollars every year for their students’ course materials. Indiana had been among the last handful of states that still allowed schools to charge these fees.

The law provides $160 million for curricular materials, but a per-student amount has yet to be determined, Indiana Department of Education officials said. The department will calculate this number by dividing the total amount that all schools report for curriculum costs by how many students are enrolled at each public school, and how many qualify based on socioeconomic status at each private school.

Education advocates agree the change benefits families, but say the state must support schools with the financial burden.

With a new school year rapidly approaching, they say more guidance is needed on how much schools will receive to make purchasing decisions and also on what counts as curricular materials under the new law, which broadly includes books, computer software, digital content, and hardware that will be consumed by a student over the course of a year.

Only time will tell if the total allocation is sufficient, said Denny Costerison of the Indiana Association of School Business Officials. It’ll be up to the General Assembly to increase the funding if necessary, which likely won’t happen until the next biennial budget session in 2025.

Schools will receive funding as a lump sum in December, according to an FAQ issued by the department.

“Textbooks don’t get cheaper, they get more expensive,” said Terry Spradlin of the Indiana School Boards Association. He noted that when Indiana first considered dropping textbook fees in the 1990s, the cost estimate was around $100 million.

The state already covers the cost of textbooks for students who qualify for free and reduced priced meals at a cost of around $39 million per year.

For all students, a per-pupil figure of about $162 would likely cover most districts’ elementary and middle school costs, said Spradlin, but fall far short of the costs for high school courses. Spradlin said that example amount came from an IDOE memo, but the department didn’t confirm.

Any excess from the lower grades could be used to pay for secondary school courses, but schools may also need to turn to their education fund dollars to cover shortages, he said. Federal emergency dollars are also an option, albeit one that expires in September 2024.

It’s important to remember that general funds must also cover the bulk of schools’ operating and personnel costs, said Keith Gambill of the Indiana State Teachers Association.

“You need to be able to provide the funding they need to operate and make sure those programs are fully realized without jeopardizing important items, which includes salaries,” Gambill said. “That’s where things can get tricky, especially for schools on a leaner budget.”

According to the FAQ, curricular materials include materials in advanced placement, dual credit, and career technical education courses, but not dual enrollment courses. Schools are allowed to charge families for lost or damaged items, and can offer insurance for technology.

Some additional guidance might be needed for items like parking passes and student identification cards, said Spradlin, as well as for co-curricular programs. Performing arts, for example, can include a variety of costs for instruments and their upkeep, as well as attire and transportation to school events.

If the course is required, or if students receive a grade for it, then it’s likely considered a course that schools can’t charge for, said Costerison. The education department’s FAQ directs schools to consult with their legal counsel for further questions about what counts as curricular material.

Charles A. Beard Memorial schools will be able to offer fee-free music programs to students this year after building a stock of instruments over the last several years, said Behny, the superintendent.

He said the new law will provide the final nudge for the district to drop the last of its fees for its cooperative programs, but added that the new funding alone may not be enough for districts just starting to eliminate fees.

Covering textbook fees cost his district around $87,000 in the first year of the program. This year, they spent around $110,000 to cover fees for 1,100 students, money saved through attrition and watching supply costs.

“It was much easier to do than I thought it would be,” he said.

Aleksandra Appleton covers Indiana education policy and writes about K-12 schools across the state. Contact her at aappleton@chalkbeat.org.