Uncertainty, a growing patchwork of policies, and virtual silence from state leaders have marked the rollout of an Indiana law requiring schools to disclose students’ requests to use new names and pronouns to their parents.

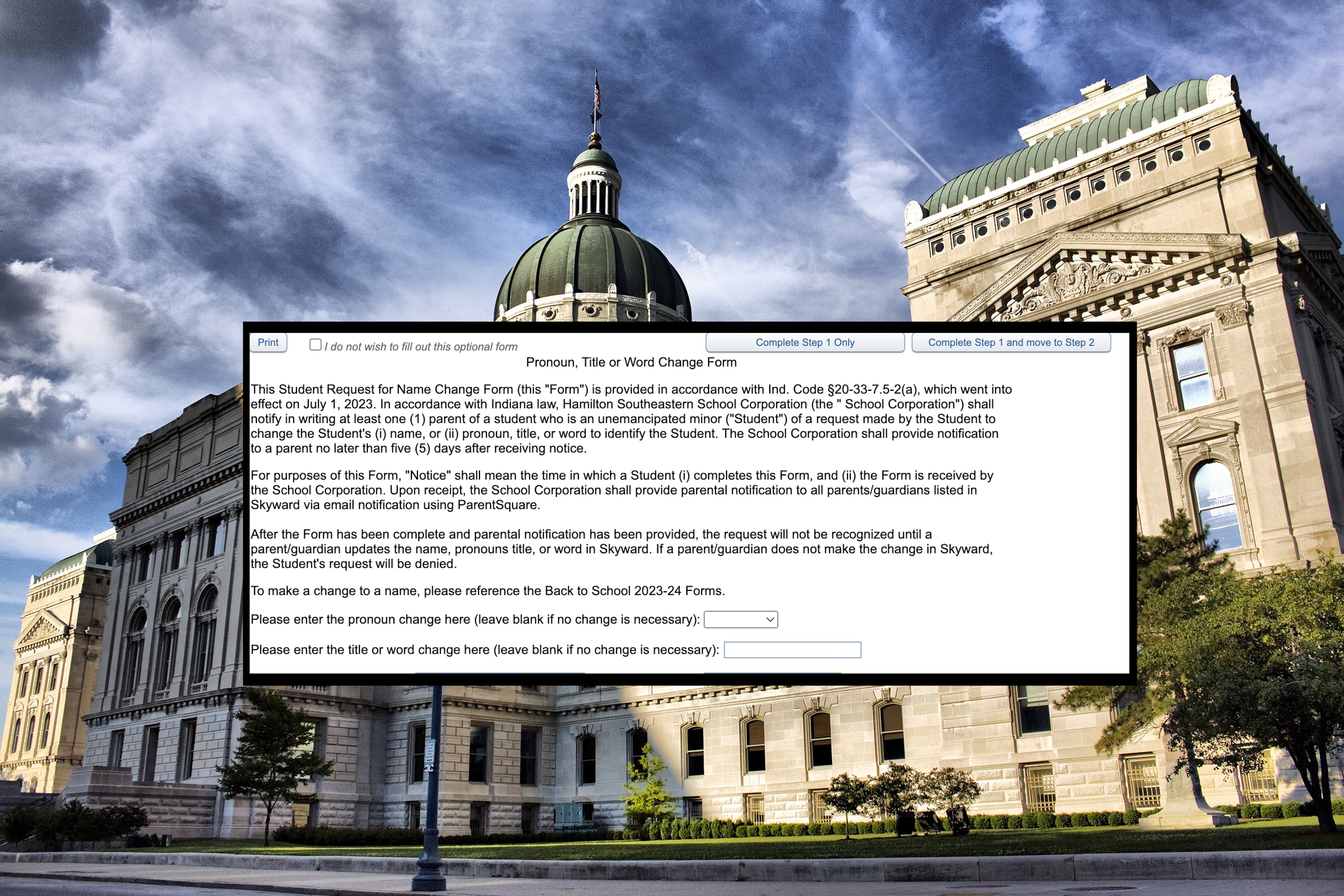

Under HEA 1608, which took effect for this school year, schools must notify at least one parent in writing if their student requests to change their name, pronoun, title, or other identifying word.

But there’s little guidance in the law or from state agencies about various issues, including how districts should notify parents. That vagueness has left students and educators on their own to figure things out.

At least one district is going beyond the law by requiring parental permission to use students’ new names — a mandate that was dropped from the original legislative proposal over concerns it might sow conflict within families. But leaders of another district who oppose the law said it has spurred them to enhance protections from harassment for students who identify as LGBTQIA+.

Different policies could leave parents unhappy regardless of what’s tried. For example, some parents might argue their districts aren’t doing enough to ensure they know about students’ requests, said Andy Downs, director emeritus of the Mike Downs Center for Indiana Politics. Yet others, he said, might believe their districts are going overboard if they send letters, schedule meetings, and repeatedly follow up with families.

With transgender rights firmly in focus on the national political scene, local school leaders searching for the right approach could spark an uproar at already contentious school board meetings.

Still, some advocates do see a silver lining in the fragmented way the law is being carried out: a chance to shape, or even challenge, how it’s applied in their local schools.

“The right thing to do is to fight the mandate,” said Barbara Dennis, a volunteer with Kaleidoscope, a Bloomington-based and youth-led LGBTQ advocacy group whose members have discussed ways to subvert the law. “But we also need to survive the moment.”

What the new law on students’ pronouns does

HEA 1608 was one of several laws Indiana legislators passed this year aimed at restricting how and when transgender youth could transition socially and medically. Proponents say it gives parents more information about their children at school — part of an argument for increased parental oversight in education that has swept conservative states.

“We’re going to fight for the right of parents to handle the upbringing of their children,” said Indiana Attorney General Todd Rokita at a recent press conference in reference to such laws.

But opponents of the new law said outing transgender students to their parents could put some at risk of physical harm or homelessness if their families aren’t supportive. (The American Civil Liberties Union of Indiana challenged HEA 1608 in court by focusing on another aspect of the law that prohibits teaching human sexuality in grades K-3.)

The law does not prescribe details like what a written notification to parents about their students’ name requests should contain, nor whether schools are required to send follow-up notices.

By contrast, another law passed this year on student surveys specifies that schools should send parents two notifications before they can administer certain surveys, that the notifications can be electronic, and that each should summarize the content of the survey in question.

The Indiana Department of Education does not plan to issue guidance on how schools should implement HEA 1608. A spokesperson said implementing the law “comes down to a local decision by the school districts.”

The department did provide guidance on a dozen or so other laws from the 2023 legislative session.

Rep. Michelle Davis, a Whiteland Republican and author of the law on student pronouns, declined to comment on how she intended it to be enforced, citing the ongoing litigation.

Downs said that some laws are written to offer as many details as possible in order to remove any doubt about compliance, while others offer leeway to the people who have to implement them.

If there are enough complaints about the law’s lack of clarity, legislators will likely take notice, Downs said.

“They may pay an awful lot of attention if constituents say they weren’t informed properly,” he said. “They may say, ‘Ok you had your chance, schools, to do this properly and you did not. So now we will.’”

Downs said that ideally, legislators would see how HEA 1608 affects schools and students, before considering whether to expand it. He also noted that some issues fade from the public eye over time, and that schools sometimes keep procedures on the books without enforcing them.

But given the emotionally charged debate around the topic, Downs said it’s most likely that legislators will revisit HEA 1608 soon.

Becoming ‘better parents for LGBTQ kids’

Speaking at a Monroe County school board meeting Tuesday night, a student told board members that they considered submitting a name change request every day in order to “maliciously comply” with the law — but reconsidered after realizing the burden it would create for teachers.

“The school board should be the ones fighting for us students,” the student said. “I shouldn’t have to fight for the right to my name.”

Dennis, the Kaleidoscope volunteer, also said it’s ultimately up to school districts to file lawsuits challenging the enforcement of the law. Complying puts youth at risk, and damages schools’ ability to support students.

“A main tactic in bullying is pointing at kids and telling them who they are,” Dennis said. “Under this law, educators will be forced to enact bullying.”

The student at the Monroe meeting addressed a board that previously criticized the law in strong terms. In March, board members approved a resolution condemning HEA 1608 and stating that the district would work on a policy that prohibits the bullying or harassment of LGBTQIA+ students.

In an August statement, the district described the law as “Trojan horse legislation,” but said its schools will comply and notify parents. It will also communicate the new requirement to students and families, according to the statement.

Work on an anti-harassment policy will continue through a series of community engagement meetings this fall, the district said. Monroe district leaders also said in its August statement they’re “confident that the new state legislation does not prevent the important work related to our local resolution to support more fully our LGBTQIA+ population. As a matter of fact, with legislation, such as Indiana HEA 1608, this work is more important than ever.”

Other districts have already announced their approaches for notifying parents. Many are designating one person at each school to notify families of their students’ requests, or having their counseling staff do the job. Some are relying on their student information portals; others are sending written notifications encouraging parents to ask questions.

Hamilton Southeastern schools — which last year elected a slate of candidates running on a parental rights platform — has gone a step beyond the law and will require approval from a parent or guardian before the district will use a student’s requested name.

“Hamilton Southeastern Schools has no desire to make student name changes to which a parent objects,” a statement from the district said, adding that federal and state law require parents and schools “to work collaboratively.”

The student members of Kaleidoscope have brainstormed other ways to push back against the law without violating it, like by using class nicknames, placards, or last names instead of students’ legal first names. But some of these approaches wouldn’t allow students to publicly claim their own identity, said Dennis.

Working under the confines of the law, districts could also interpret the mandate to “notify” parents to mean setting up a conference between schools and parents to discuss their students’ requests and how best to support them.

“If the goal is to be better parents, maybe we can take this as an educational moment to become better parents for LGBTQ kids, and foster areas where kids feel safer,” she said.

Aleksandra Appleton covers Indiana education policy and writes about K-12 schools across the state. Contact her at aappleton@chalkbeat.org.