Sign up for Chalkbeat Indiana’s free daily newsletter to keep up with Indianapolis Public Schools, Marion County’s township districts, and statewide education news.

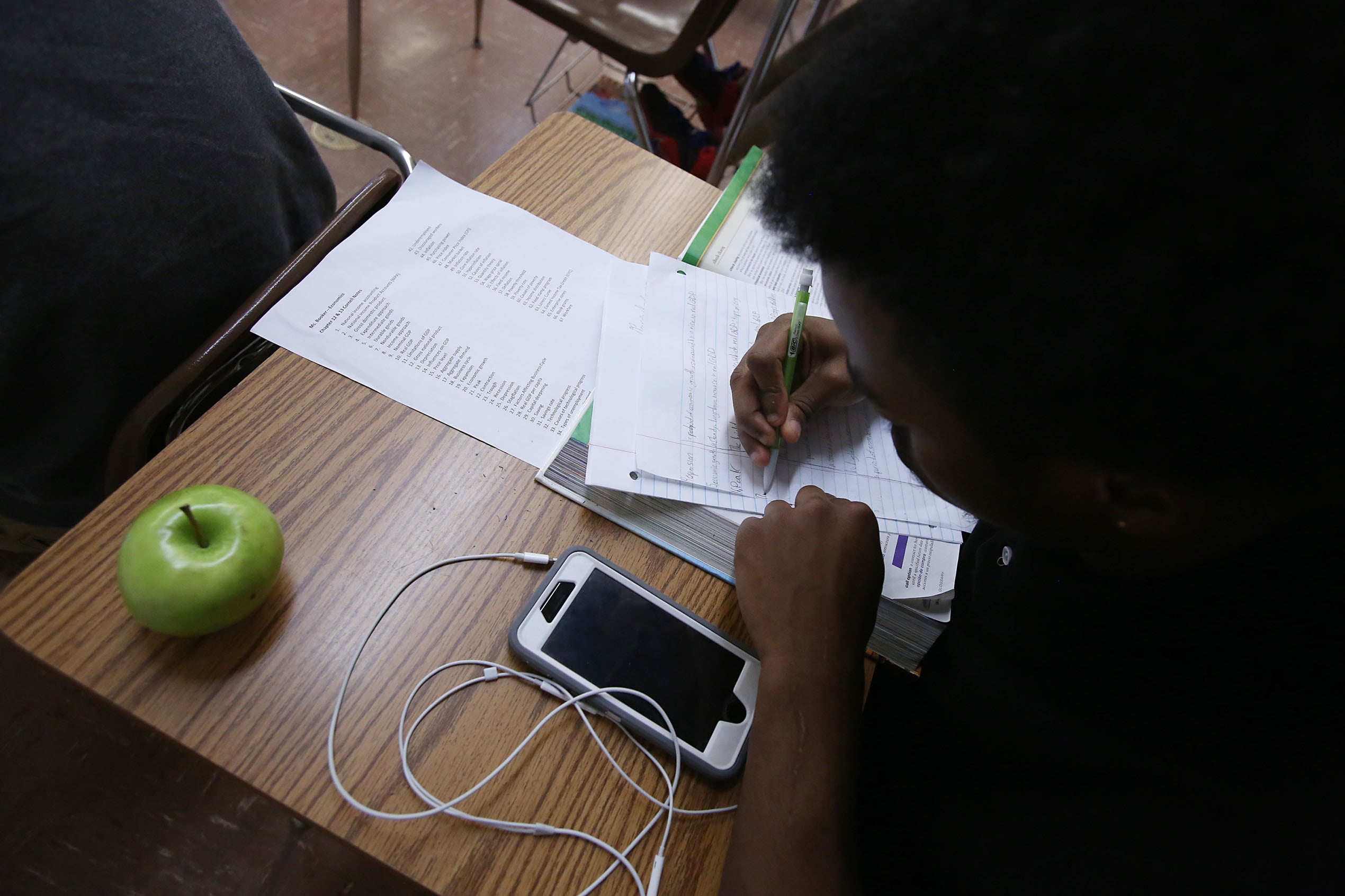

Indiana students will need to put their phones away during class starting next school year, under a new law that requires districts to ban communication devices from classrooms.

Senate Enrolled Act 185 bans “any portable wireless device.” The bill — which was signed into law Monday by Gov. Eric Holcomb and takes effect in July — requires districts, including charter schools, to adopt policies banning several types of devices during class time.

Lawmakers and advocates hope the ban improves student engagement, behavior, and mental health, all of which they say have declined since cell phones became a common sight in students’ hands. They’re part of a national push to enact bans on cell phones in schools.

“Even as adults, we’re distracted by using our cell phones,” said Sen. Jeff Raatz, a Republican and the bill’s author, in a Feb. 14 meeting of the House Education Committee.

Here’s what you need to know about the upcoming cell phone ban, including exceptions to it, what schools have previously done to limit cell phones, and concerns about it.

How does the new cell phone ban work?

Under the new law, school districts will need to adopt policies banning communication devices during instructional time. That includes phones, tablets, laptops, and gaming systems, as well as any other devices that can provide communication between two parties.

Exactly how that will be done is up to each individual school district. Students might be required to put their phones in locked pouches or designated places in the classroom.

It will be up to school boards to adopt these policies this summer.

However, the law says a student can use their device:

- if a teacher allows it for educational purposes during instructional time.

- if a student needs to manage their health care, as for blood sugar monitoring, for example.

- in the event of an emergency.

- if the use of the device is included in their Individualized Education Program or 504 plan.

The law does not define what constitutes an emergency.

The exception for instructional time is important for students in dual credit programs, said Mary Jane Michalak, vice president of legal and public affairs at Ivy Tech Community College, because it will allow them to access two-factor authentication.

Why do people want a cell phone ban?

Lawmakers attempted to ban cell phones in schools over two decades ago, said Rep. Vernon Smith. However, the law was reversed due to safety concerns.

The rapid adoption of phones between 2010 and 2015, coupled with the development of more attention-grabbing apps, has led students to spend more and more time on their phones, said Evan Eagleson, regional advocacy director for ExcelinEd, during testimony.

Eagleson said studies have shown students spend seven to nine hours a day on their phones, receiving around 237 notifications — a quarter of which occur during class time.

Since COVID, teachers report that student behavior and mental health issues linked to cell phones have spiked, said John O’Neal of the Indiana State Teachers Association in testimony.

“It’s becoming a major problem,” O’Neal said. “Students aren’t motivated in class because they’re distracted by their devices.”

How do educators and parents feel about it?

While schools already have the power to ban cell phones, such prohibitions have largely been left to the discretion of individual teachers, the bill’s supporters said, creating inconsistency from classroom to classroom.

A statewide law provides consistency and helps to enforce existing local policies, said Terry Spradlin, executive director of the Indiana School Boards Association, during testimony on the bill.

Education groups that supported the new law include the Indiana State Teachers Association, the American Federation of Teachers, the Indiana School Boards Association, and the Indiana Association of School Principals.

While the bill saw little opposition from advocates or lawmakers, some noted the potential increase in school discipline for students who try to circumvent their districts’ new policies. The enforcement of the ban, as well as any potential consequences for students who violate it, will be up to school districts.

Parents, too, have expressed concerns about being able to reach their students in the event of a school emergency.

How have schools tried to limit cell phones?

Spradlin said school districts’ existing guidelines on cell phone use typically ban the devices from classrooms, or leave it up to teachers. They often permit cell phone use during lunch and passing periods.

But a few Indiana districts have recently moved to ban cell phones during the school day. Fort Wayne Community Schools announced in February that it would pilot “phone-free schools” at two of its middle schools and two of its high schools this spring.

Students will be required to put their phones in locked pouches, which will be unlocked at the end of the day.

Hammond and Martinsville schools also adopted policies at the beginning of this school year requiring students to put their phones away.

Clarification: This story has been updated to reflect the law includes both traditional public school districts and charter schools.

Aleksandra Appleton covers Indiana education policy and writes about K-12 schools across the state. Contact her at aappleton@chalkbeat.org.