Sign up for Chalkbeat Newark’s free newsletter to get the latest news about the city’s public school system delivered to your inbox.

Nine low-income New Jersey school districts bucked national trends and are now performing above pre-pandemic achievement levels in reading, math, or both.

That’s shown in a new release of the Education Recovery Scorecard, which compares learning loss and recovery across thousands of school districts nationwide.

The districts include Union City, Woodlynne, Lakewood Township, Ventnor City, Commercial Township, Englewood, Garfield, Hillside, and Beverly City.

Superintendents in those districts and researchers attributed the success to academic catch-up efforts, such as high-impact tutoring and summer learning opportunities. Now, these districts are working to continue offering effective interventions as pandemic relief funds dry up and President Donald Trump warns of cuts to education funding at the federal level. Thomas Kane, a professor at Harvard University, suggested that all school districts should use other local, state or federal funds to continue offering these programs whenever possible.

“Unless state and local leaders step up now, the achievement losses will be the longest lasting — and most inequitable — legacy of the pandemic,” Kane said.

The average New Jersey student is two-thirds of a grade level below 2019 levels in math and almost half of a grade level below pre-pandemic levels in reading.

New Jersey had among the biggest drops in math performance for low-income students, according to the annual scorecard report from researchers at Harvard and Stanford universities. The average student in West Windsor-Plainsboro, Edison Township, Hamilton Township, Newark, Paterson, New Brunswick, and Trenton remains more than a full grade equivalent below their 2019 mean achievement in math.

Districts with the highest incomes were four times more likely to recover to pre-pandemic levels than the lowest-income districts, with federal relief dollars preventing those gaps from growing even wider, researchers said. Districts serving more Black and Hispanic students are falling further behind, and even within those districts, Black and Hispanic students are falling further behind their white district peers, said Sean Reardon, a professor at Stanford University.

The researchers highlighted Union City as a “district success story” for passing pre-pandemic achievement in math and reading. Montgomery Township, Princeton, Rutherford, Montclair, and Livingston are also considered “fully recovered” by the researchers.

Remote learning kept students ‘much more disengaged’

Low-income communities were generally less prepared for online learning than wealthier communities when the pandemic caused schools to close in March 2020. Even if a district had laptops for each child, access to Wi-Fi or quiet spaces sometimes posed problems.

Rutherford Public Schools Superintendent Jack Hurley said opening schools for in-person instruction during the 2020-2021 school year helped limit drops in academic recovery. Even when schools closed in March 2020, forcing districts to adopt online learning, the district was prepared since each student already had access to a Chromebook laptop. Rutherford is not classified as low-income and saw gains in both reading and math that surpassed pre-pandemic levels.

Every student in Beverly City School District, which is low-income, also had a laptop, which Superintendent Elizabeth Giacobbe said prevented students from losing too much ground. The district opened its doors for full-time, in-person instruction for the 2020-21 school year with a remote option available for families who wanted it.

“The students that came every day, Monday through Friday, from eight to three, benefited greatly from having the social interactions,” Giacobbe said. “Those that chose to stay at home were much more disengaged.”

On the other hand, the low-income Englewood Public School District was one of the last in the state to return to in-person instruction, which was not beneficial to students or teachers, Superintendent Marnie Hazelton said.

The district had laptops for each child, but there was a lack of Wi-Fi availability when students started attending school remotely. The district spent some of its federal relief money on creating Wi-Fi hot spots and improving internet connectivity. Englewood recently joined a Verizon program that provides the district with 1,400 LTE-enabled Chromebooks that allow students access to the internet from anywhere.

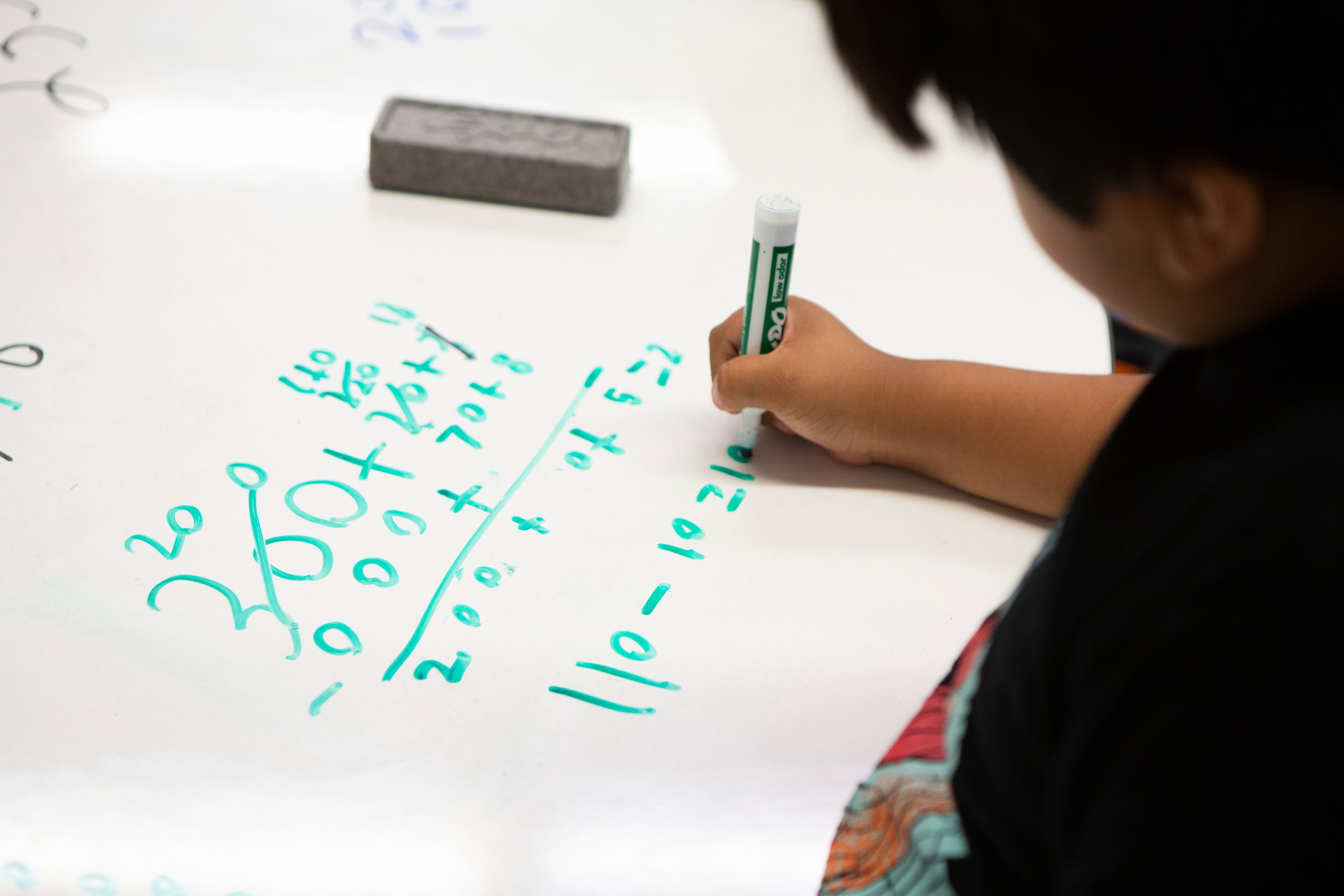

Promoting tutoring programs increased demand

Englewood used high-impact tutoring and free summer learning programs to curb learning loss, with a focus on the most vulnerable students.

“We have been very intentional about targeting or focusing on our most fragile students, looking at those students that are in that subgroup of free and reduced [lunch program],” Hazelton said. Students from low-income backgrounds exhibited more growth than students in the district who were not from low-income families, although their performance remains lower.

Englewood received the state’s high-impact tutoring grant, which was designed to help third and fourth graders recover from the pandemic. At first, Hazelton said the program did not reach capacity but after outreach to parents whose kids would benefit, there is now a waitlist.

Additional instructional time, including before and after school, on the weekends and over the summer, is common across the districts that made up ground lost during the pandemic.

Kane, the researcher from Harvard, said it’s important to keep parents informed about how their students are doing so they take advantage of such programs. He noted that more than 90% believe their kids are at grade level, which is not true.

“Parents aren’t going to sign up for summer learning or ask for a tutor in school or agree to an increase in the school year if they’re under the impression that everything’s fine,” Kane said.

Rutherford also offered summer enrichment and before and after school programs to help students catch up. Pandemic relief funding allowed the district to create a “zero period” at the start of the day when kids could receive extra help. That program is over now, but the summer academy is continuing to grow with funding from other sources.

Chronic absenteeism slows down academic recovery

New Jersey school districts also saw a rise in chronic absenteeism, which is when students miss more than 10% of a school year. In 2019, 11% of students were chronically absent, compared to 16% in 2023. This is slowing the recovery in many districts, the researchers said.

Beverly City School District in Burlington County saw a jump in absenteeism from 8.7% in 2019 to 43.2% in 2022. By the following year, absenteeism dropped to 24.2%.

Giacobbe said the district identifies chronically absent students and assigns them case managers who regularly check in with the students and their families or caretakers. Case managers try to work with the parents to come up with a solution, but if they are unsuccessful the district will file truancy charges, Giacobbe said.

The district also tries to get students to come to school by offering incentives, such as dress-down days and flexible seating at lunch.

Kerri Lawler, director of curriculum and instruction in the district, said the nurse plays a big role by offering flu clinics and washing clothes for students to eliminate barriers to attendance.

Kane suggested school districts get outside help from the community to reduce absenteeism. In districts where absenteeism grew substantially, it hurt academic recovery.

“We all know we need kids in school to learn,” said Alexandra Bellenger, director of curriculum and instruction for the Garfield School District, a low-income district that passed pre-pandemic achievement levels in reading. “If they’re not here, they’re not learning.”

Cuts to tutoring programs loom

Bellenger’s district offered after-school tutoring and enrichment, summer programs, and Saturday programming for students to help with recovery. Much of this was funded with federal relief dollars, but Bellenger said the district is working to continue initiatives by paying for them in other ways, such as through Title I dollars that support high-poverty schools. She said the district is taking a data-driven approach to decide which programs to continue funding and which students to target for extra support.

Kane of Harvard University said that due to the flexibility of how pandemic relief dollars could be spent, they had about the same impact as an increase in general revenue for a district. Dollars spent on academic catch-up, such as tutoring, summer learning, and after-school learning had larger effects, he noted.

“On average it looks like the dollars did have an effect and they particularly helped narrow the gaps or prevented the gaps from being even worse between high and low-income districts,” Kane said.

New Jersey received $4.3 billion in federal pandemic relief for K-12 schools, which is an average of $3,100 per student. This is below the national average of $3,700 per student, although federal dollars varied significantly even among low-income school districts. For example, Garfield received an average of $2,805 per student from the Elementary and Secondary School Emergency Relief fund while Ventnor City received $9,038.

In Ventnor City Public School District, Superintendent Carmela Somershoe said the district used relief funds to offer a summer program with small classes that reached students based on need. Now that the money has dried up, the district is incorporating intervention into the regular school year instead of offering summer programs. This includes using Title I funds to pay for an academic after school-program and reading intervention.

Somershoe said the district is trying to budget carefully and intentionally due to the unpredictability that comes with each budget season and a new presidential administration.

Hazelton said Englewood is preparing for a flat budget for the next school year, noting the district may have to prepare for layoffs. She said programs like high-impact tutoring and summer learning have made a huge difference, and she plans to favor those in the budget even if it means higher class sizes during the school year.

The district is also working to improve its capacity for special education, to accommodate more students in district schools instead of having them attend approved private schools for students with disabilities, which cost districts a lot of money between tuition and transportation.

New Jersey school districts are set to find out how much money they will receive in state aid on Feb. 27, two days after the governor’s annual budget address. Districts must submit their budgets in March.

Hannah Gross covers education and child welfare for NJ Spotlight News via a partnership with Report for America. She covers the full spectrum of education and children’s services in New Jersey and looks especially through the lens of equity and opportunity. This story was first published on NJ Spotlight News, a content partner of Chalkbeat Newark.