Four days after the killing of George Floyd by the Minneapolis police, a Brooklyn Success Academy teacher emailed her network’s CEO, one of the nation’s most prominent charter school leaders, asking why she hadn’t said anything publicly.

“I am deeply hurt and shocked by your lack of words on the topic that affects so many of your employees, children and families in communities that you serve,” first-year Success Academy Flatbush teacher Fabiola St Hilaire wrote to Eva Moskowitz. “All of your black employees are paying attention to your silence.”

Moskowitz responded about an hour later, thanking St Hilaire for reaching out but also brushing her aside. “I actually opined on this subject early this am. Please take a look,” Moskowitz wrote, referring to a tweet sent the same morning. “I hope you can understand that running remote learning in the middle of a world economic shutdown has kept me focused on [Success Academy’s] immediate needs.”

Upset by the response, St Hilaire posted the email exchange on social media, thrusting New York City’s largest charter network into a wider debate about institutional racism. Some current and former employees were angry that Moskowitz seemed to dismiss the concerns of an educator of color as well as the broader movement to reckon with structural racism in the aftermath of Floyd’s killing.

As other big charter networks took the unusual step of cancelling class for a day to give students and staff time to grieve and reflect, Success waited several days before following suit. Some staffers felt Success was unprepared to meet the moment, and Moskowitz’s exchange with St Hilaire morphed into a larger critique of the network. It sparked dozens of mostly anonymous Instagram comments — often touching on race — from employees, parents, and students.

The posts describe calling 911 on students with behavior problems, policing Black students’ hair by banning certain headwraps, and a culture where white educators are comfortable dressing down parents of color for minor issues like arriving late to pick up their children. Half of the teachers and principals at Success are white, 27% are Black, 13% are Hispanic and 5% are Asian. Meanwhile, 83% of the network’s roughly 18,000 students are Black or Hispanic and most come from low-income families.

“This is all long overdue,” a current Brooklyn Success teacher told Chalkbeat on condition of anonymity, referring to the debate about some of the network’s practices. “I’m hoping that if we get enough people to rally from within, something can actually be done.”

The network’s leaders have shifted to damage control mode, with Moskowitz putting out more forceful statements condemning racism and police brutality, holding virtual town halls to respond to parents and staff, and taking the unusual step of cancelling a day of class to give students and staff space to process Floyd’s death. Moskowitz even echoed activists’ calls for removing the police department from New York City schools.

A Success spokesperson pushed back against the online complaints, writing in an email that they “are being made by a handful of former employees and families. Our current employees and families overwhelmingly support our schools.”

At a town hall meeting this week with staff, Moskowitz said she “stands in solidarity with all of the protestors” and apologized for not responding more swiftly to Floyd’s killing, according to a recording obtained by Chalkbeat.

“I was late, and I really regret that,” she said. “There was no attempt to be silent on the issue. I feel very, very strongly that Black lives matter.” (Moskowitz said she had needed time to craft a response, though one educator later noted she sent a letter to the Success community the day after NBA superstar Kobe Bryant died in a helicopter crash.)

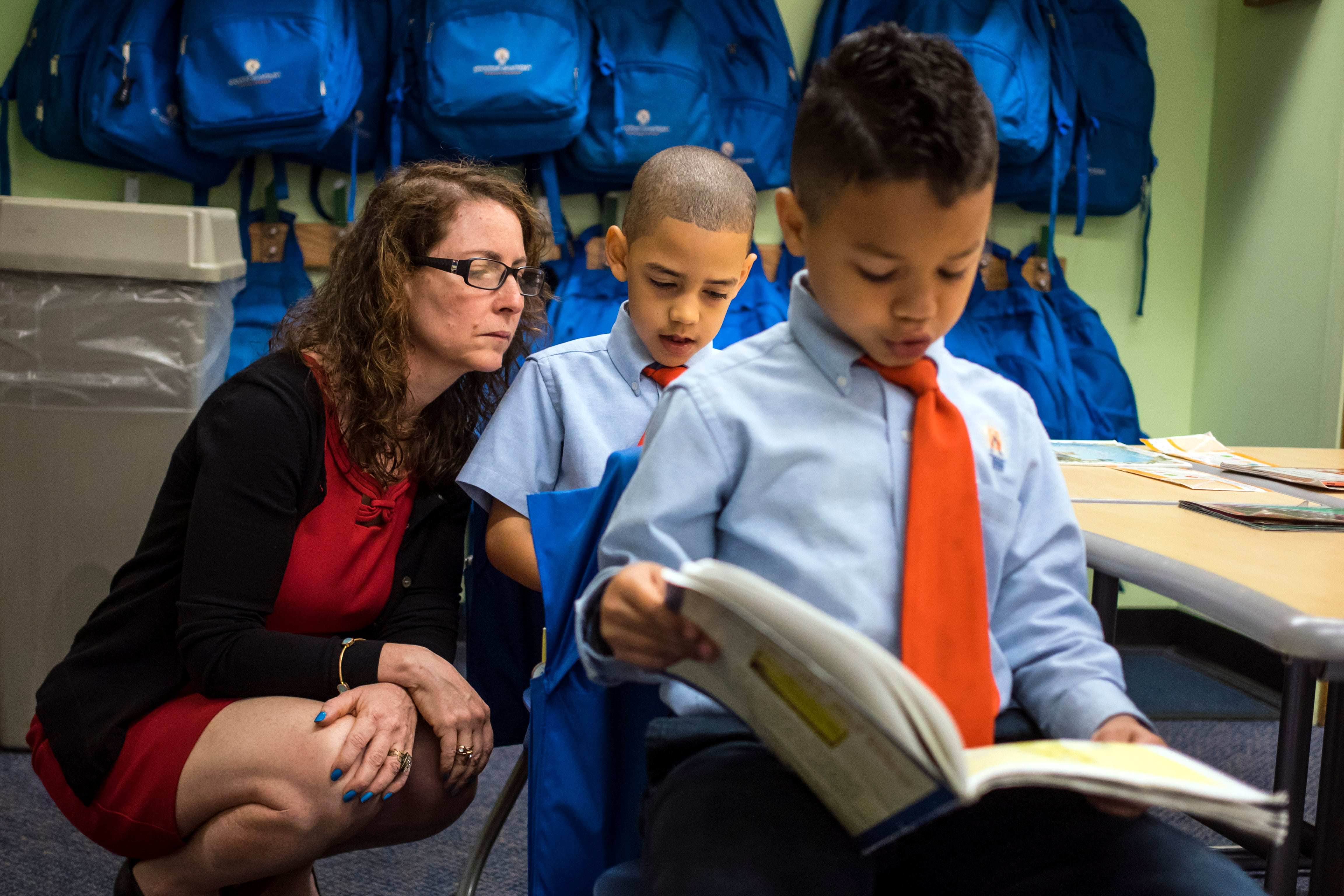

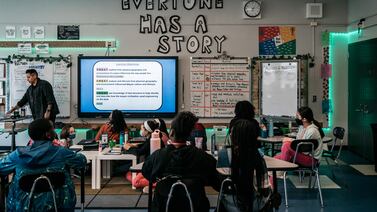

The broader complaints also get at the heart of the network’s “no excuses” philosophy, a mix of strict discipline and high academic expectations. In class, students are often required to sit with their hands clasped, consistently track teachers with their eyes, and are regularly corrected for any deviation from the rules. Some current and former Success teachers said they’ve become increasingly uneasy with the enforcement of behavior expectations and have even come to see them as racist.

“The number of young Black males you’re suspending is part of the problem — you’re suspending them for non-compliance, for having tantrums. That’s a cry for help,” said Erika Johnson, a five-year Success Academy educator who left last year to teach fourth grade at a KIPP charter school in Massachusetts. She said she signed on to an online petition calling for a broader reckoning with Success’ culture and more specific actions like anti-racism training.

“The change needs to start with Eva and the network office,” Johnson said.

Many charters that embraced similar “no excuses” models have in recent years moved away from the approach, reducing suspensions, changing the way teachers respond to small infractions and relaxing dress codes.

But Moskowitz has vigorously defended her network’s strict approach arguing that exacting behavior expectations that are consistently enforced provide a necessary condition for student learning. And network leaders argue it works: Success’ students, the vast majority of whom are Black or Latino, typically outperform much whiter and more affluent districts on state tests. Parents of color continue flocking to Success, and network leaders are honest about what will be expected of them and their children.

“There is no doubt in my mind that there is a significant appetite among low-income parents for exactly the flavor of education that Eva Moskowitz offers,” said Robert Pondiscio, a senior fellow at the conservative-leaning Fordham Institute who spent a year observing a Success elementary school in the South Bronx and wrote a book about it. “It just does violence to reality to pretend that this is some kind of pedagogy that’s being imposed on families of color.”

At the same time, he isn’t surprised that some employees may be increasingly uncomfortable with the responsibility of enforcing strict behavior expectations on students of color, even if they are designed to foster student achievement.

“A lot of those techniques — rightly or wrongly — may feel oppressive to a new generation of young people, and I think that’s a vulnerability for high-performing charter schools,” Pondiscio said.

There are other signs network leaders are worried about the conversation swirling online. On Monday, Moskowitz directly responded to a single Instagram post that leaked a description of a 2015 ad that Success Academy was involved in producing.

A production schedule for the ad, designed to draw a contrast between the types of schools available to white and Black students, described the scene with white students as a “good” classroom and Black students in a “bad” classroom. After facing questions about that description, Moskowitz sent a letter to staff Monday saying that the terms “good” and “bad” were meant to describe the physical classrooms, not the children.

“If the person had been explaining the meaning of these scenes, I would hope they would have made the underlying message clearer by writing ‘a white child is filmed sitting in a nice classroom with a colorful bulletin board and pictures while an African American child is shown in a dreary classroom to illustrate that African Americans aren’t given equal educational opportunities,’” Moskowitz wrote. “That was clearly the ad’s message.”

At the town hall meeting with staff on Monday, Moskowitz argued that the network’s mission is fundamentally anti-racist.

“I imagined that if you could educate tens of thousands of students, mostly of color, especially well, they would get into the halls of power, and they would most effectively combat institutional racism,” she said.

Some parents said they are frustrated that Moskowitz leans on them so heavily to help advocate for the network, but when it comes to issues bubbling up in their communities, she is often absent.

“The parents did try to get together and rally when we needed a middle school and she came out for that,” said a parent at Success Academy Far Rockaway who spoke on condition of anonymity, referring to Moskowitz. “But she never comes out any other time.”

The parent said she has complicated feelings about the network: Her son was suspended several times in kindergarten, which required her to miss work or find other childcare, sometimes paying out of her own pocket. But she generally likes her son’s teachers and is drawn to his school’s academic rigor.

“Yes we love the academics, but their ways and their methods — [we] are starting to stand against it,” she said. “There needs to be some change.”