Throughout elementary school, I would come home, change out of my uniform, open my workbook on a child-size wooden table, complete my assignments, and bring the book to my mom. Only after she rigorously double-checked my work could I plant myself down in front of the TV.

Even throughout middle school and high school, I was reluctant to mention my assignments to my mom; if she knew a paper was due, she would demand to read it, and 10 minutes later, every available space on the printed page would be marked with more words, strikethroughs, arrows, and circles.

My mom isn’t the type of person who gives the edits back and lets you go about your day. She would stay by my side at the computer, going through each edit and explaining the change. The process, sometimes agonizing, could go on for hours. But it made me a strong writer and a person who strived to succeed.

In the second grade, my mom thought it was time for me to move on from the private school that she felt was not providing me with enough opportunities for educational and social growth.

“The most challenging thing for me was finding an elementary and middle school for you and your brother that offered a solid education program that included music and art and other extracurricular programs,” my mom recalled of her search for a public school.

But her expectations didn’t end there. She wanted us to be in a school with an “organized, friendly, compassionate and accessible principal” and excellent teachers and staff. She wanted the school to be culturally diverse and to have a parent-teacher association (in addition to a parent coordinator). She wanted my brother and me to experience class excursions in and beyond the city: Radio City, Ellis Island, overnight trips to other states.

Once I switched to public school, my mom was a regular at evening parent-teacher association meetings. For me, that meant late-night recess. While I ran around classrooms and hallways with friends, she discussed her concerns and offered suggestions for improving the school.

When choosing a middle school, I hoped to attend In-Tech, a 10-minute walk from my house in Riverdale. It had a large campus, with a running track and updated technology so students could learn computer programs and coding. However, because of my address, I narrowly missed the school zone boundaries that would have essentially guaranteed me a spot in the school. A friend who lived down the street, for example, was zoned for In-Tech and accepted there.

My mom and I spent so much time trying to get into In-Tech that the seats in other neighborhood schools were filled. Instead, I rode two city buses for an hour each way to get to my middle school in the East Tremont section of the Bronx, situated on the same block as a power plant transformer and a methadone clinic. Safety was a major concern, especially when I started commuting alone.

School zoning meant, for the first time in my life, that my mom wasn’t in control of my education. I wanted to attend a school with updated buildings, resources, and strong academic and extracurricular programs, but those things felt inaccessible.

Sometimes, I wondered why it seemed more important to do well on these tests than to think critically and really understand the content.

For high school, I was eager to attend school outside of the Bronx, as I imagined schools in Manhattan would provide the opportunities I lost in middle school. The reality was disappointing. My Manhattan high school had advanced technology, updated textbooks, and a variety of academic courses, Advanced Placement classes, and extracurricular activities. But standardized testing outcomes were a priority. Practice tests and mini assignments that replicated sections of the exams were constantly distributed as classwork and homework. Sometimes, I wondered why it seemed more important to do well on these tests than to think critically and really understand the content.

But I never thought to push back against this idea. I didn’t know any of us, students or parents, had a say in the matter.

When I first learned about Chalkbeat, I realized that parents like my mom do have a right to question and challenge schools for the benefit of their children’s education. Teachers have a right to offer suggestions and plan lessons according to their students’ needs. And students have a right to share their thoughts about the education they are getting. Their voices matter and deserve to be heard.

As Chalkbeat’s community listening and engagement intern, I’m listening.

This summer, I will be reaching out to students, parents, and teachers around the country to hear about the issues impacting their lives, schooling, and neighborhoods. Over the next few weeks, I will be sharing Chalkbeat surveys; please tell us what’s working, what isn’t, and what changes you think would make a difference. Currently, I have two open callouts: What does LGBTQ+ representation in literature mean to you? and High school seniors, has the pandemic affected your perspective on higher education?

I want to engage with existing Chalkbeat readers and help the news organization reach new audiences, too. If you have a question for our team or a story about schools, please email me at ejohnson@chalkbeat.org. I can’t wait to hear from you.

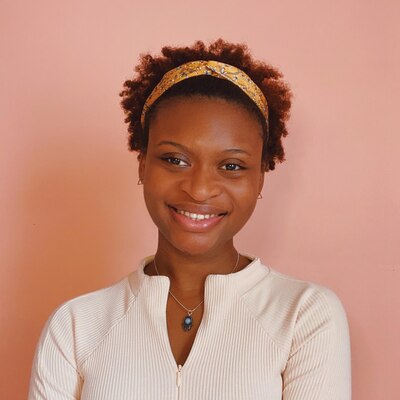

Elena Johnson is a recent graduate from The City College of New York. She studied English and journalism and enjoys sharing empowering stories about people’s experiences and lifestyles.