New York City’s fight over school budget cuts has dominated the news. But at the heart of that debate is declining student enrollment.

Overall, K-12 enrollment has dropped by 9.5% since the pandemic began. Officials are expecting 30,000 fewer K-12 students to be on the rolls this fall compared to last year.

In this most recent school year, three-quarters of schools saw fewer students, a Chalkbeat analysis previously found. Enrollment of Black and white students dropped by 7.5% each, while it dropped by 5% for Asian American students and 4.5% for Latino students.

Enrollment numbers have been declining steadily since the 2015-16 school year – before the steep drops during the pandemic, according to the city’s Independent Budget Office, or IBO.

But there’s also little evidence that families are fleeing traditional public schools for charters or private schools.

Student enrollment has big implications for public schools. Projected declines have already impacted school funding this year. And fewer students could mean tough decisions about school closures and mergers, which education officials have not yet discussed.

Here’s an overview of what is happening with enrollment in New York City:

How does NYC’s enrollment drop compare to the rest of the country?

Enrollment in public schools nationwide dropped by 1.2 million students, or about 2%, between the fall of 2019 and the fall of 2020, according to the Return to Learn Tracker, which collects state level data. (This figure does not include prekindergarten).

That tracker shows an additional 91,000 students did not show up to public schools in the fall of 2021. That would put the total drop in enrollment at 1.27 million children nationwide since the pandemic started.

Compared to the national numbers, New York City’s declines are striking and likely have led to the state’s dubious distinction: With 6% fewer students in schools statewide since the pandemic began, New York has seen the biggest declines of any state, according to the tracker.

Enrollment is not dipping evenly across all grades.

To understand why enrollment may be dropping, it’s first important to know which grades are seeing fewer students.

In the 2020-21 school year, most grades in the city’s traditional public schools saw enrollment declines, except for eighth, 10th, 11th and 12th, according to the IBO. The most steep drop was in pre-K for 4-year-olds and kindergarten.

Then, last school year, every grade saw fewer students except the city’s free preschool program for 3-year-olds, which more than doubled as seats have expanded. The biggest decreases were in third grade, followed by sixth grade. First and fifth grades were next. In turn, some of the smallest declines were among pre-K for 4-year-olds, kindergarten, and high school grades except for tenth grade.

However, when comparing to pre-COVID, the largest enrollment drops last year were in pre-K for 4-year-olds, followed by second grade, then kindergarten, third grade and first grade. Nationwide, kindergarten enrollment dipped following the start of the pandemic, but districts began reporting some rebounds this past school year.

Enrollment in New York City’s pre-K and elementary grades ranged between 82% and 88.5% of what they were before the pandemic, the IBO found. Starting in seventh grade through senior year of high school, enrollment ranged between 89% to 99% of what it was pre-pandemic, with the highest levels in the high school years.

So, while enrollment has dipped across every grade since 2019, changes are more pronounced among early grades, despite the availability of free preschool in New York City.

Are students leaving the school system, or are parents choosing not to enroll their children?

The answer is probably both.

Last year, a team of researchers estimated that, after the first year of the pandemic, about a quarter of the nation’s enrollment loss was linked to schools that didn’t offer in-person learning. Remote learning policies specifically dissuaded families of younger children, while it had no significant impact on older students.

A Chalkbeat and Associated Press analysis also found that enrollment among white students dipped more in states where most students were learning virtually.

That could help explain some of the drop in New York City during the 2020-21 school year, when schools were not yet open full time.

“Parents demonstrated they didn’t want kids at that age sitting in front of a computer,” said Thomas Dee, a professor in Stanford’s Graduate School of Education who was part of the research team. He also noted that families wanted a safe in-person option. That could have meant families home-schooled or delayed enrolling their children in preschool or kindergarten.

So what accounts for another drop in enrollment this past school year, when buildings were open full time?

Parents again may have been delaying the start of school for preschool and kindergarten-age children, Dee said. Or parents may have felt more comfortable moving younger children to a new school. Some families might have moved because of the city’s rising cost of living.

City officials have previously linked enrollment declines, in part, to declining birth rates.

A Chalkbeat analysis found that the greatest drop in enrollment happened in schools with the smallest share of low-income students. But, the second biggest drop happened in schools where between three-quarters to all students were poor. Enrollment among low-income students fell nearly 7% this year, more than double that of students who are not considered low-income.

With the rise of remote work, it’s also possible that families are moving to a new place — perhaps to be closer to family or live somewhere more affordable.

Contrary to some theories, there’s no evidence that families are fleeing public schools in droves or for charters and private schools. While the city’s enrollment dropped by about 100,000 students since 2019 — not counting 3K — overall enrollment in city charter schools has grown by just over 10,000 students, or by 7.8%, since the pandemic started. And over that same time period, the city’s private schools actually saw a 3.6% drop in pre-K-12 enrollment, according to state data.

Dee said it’s also possible that more families are home-schooling, and not all of them have registered with the state. Homeschooling nearly doubled, to 14,000 students in New York City, with the largest increases in districts with higher shares of students living in poverty.

Demographic changes, Dee noted, may also play a big role. New York State had some of the largest population declines last year, particularly among school-age children, he said.

“No social behavior has only one cause, and I think as more data become available, we are starting to realize the broader trends that influence the character of enrollment decline and flight from places like New York City,” he said.

What can districts do to build up enrollment?

Mayor Eric Adams and schools Chancellor David Banks have raised alarms about the city’s enrollment numbers and have promised to entice families to choose public schools.

Asked how the administration is planning to do that, a spokesperson pointed to various initiatives the city has rolled out, including rethinking literacy instruction and programs for students with dyslexia, expanding gifted and talented programs, piloting a new Asian American and Pacific Islander curriculum and including parents in the hiring of superintendents, which had a bumpy rollout.

“Chancellor Banks, his leadership team, and every district superintendent is focused on reversing dropping enrollment in our public schools,” Nathaniel Styer, a spokesperson for the education department, wrote in a statement. “This work is informed by listening to families and school communities as well as putting in place policies that will ensure our public schools are the destination of choice for all of our students and families.”

There are a few things that parents typically focus on when it comes to choosing schools for their children, Dee said.

First, parents are attracted to school quality. For many families, that can mean ensuring that schools have high-quality curriculum, well-trained and effective teachers, and often, smaller class sizes, which Dee noted can be a pricey endeavor.

Recent budget cuts due to declining enrollment will likely result in higher class sizes. State lawmakers passed a bill to reduce class sizes in the city’s public schools, but the Adams administration has opposed it, and Gov. Kathy Hochul has yet to sign it.

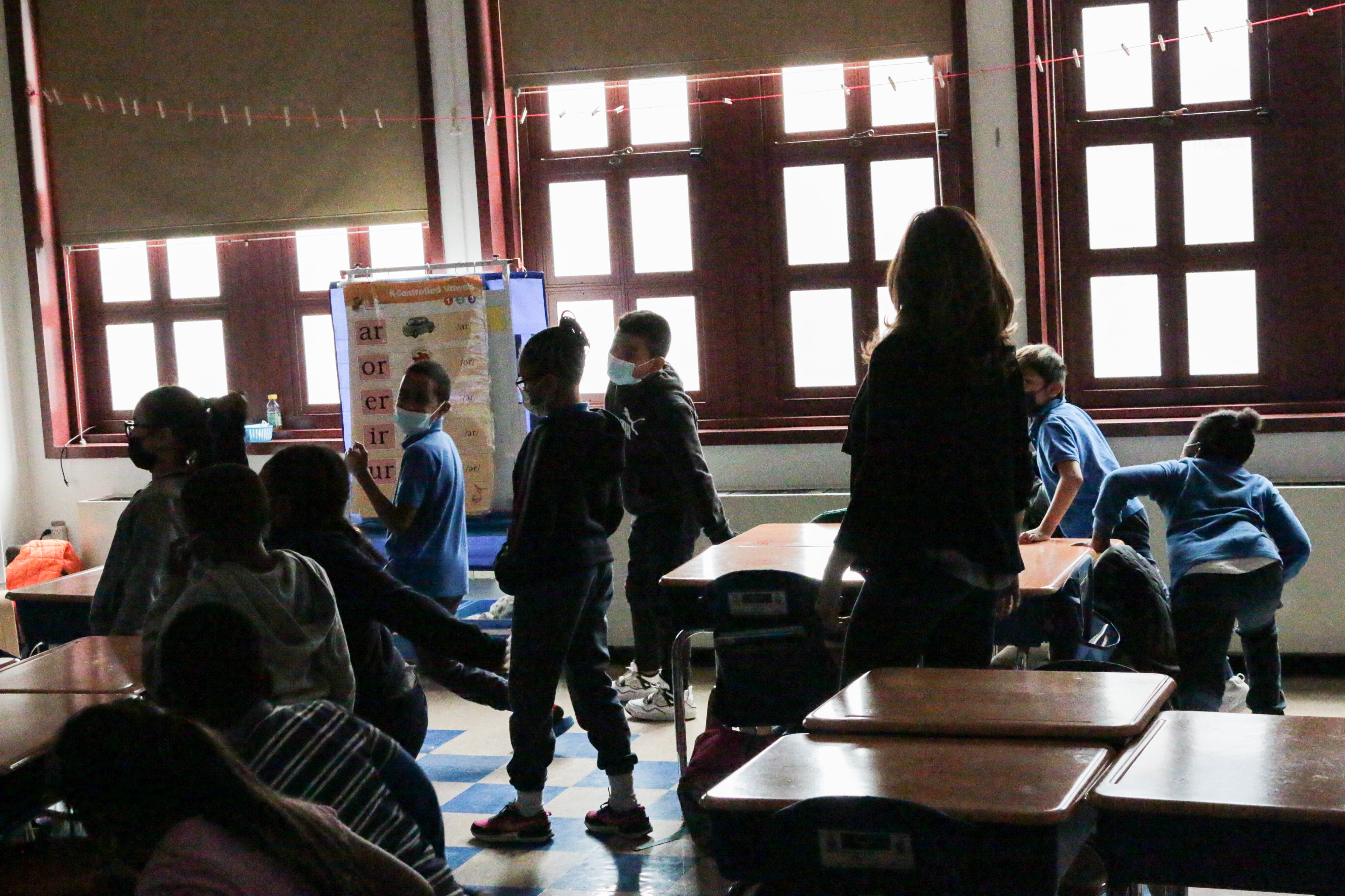

Families also care that classrooms are “welcoming, inclusive, supportive spaces” for students, Dee said.

From his research, Dee found that parents of young children wanted safe in-person instruction, so he suggested improving COVID mitigations at schools. That includes ventilation and filtration. The city has been shedding safety measures, such as universal masking and social distancing, and city officials have not yet released their safety plans for this fall.

Reema Amin is a reporter covering New York City schools with a focus on state policy and English language learners. Contact Reema at ramin@chalkbeat.org.