Sign up for Chalkbeat New York’s free daily newsletter to keep up with NYC’s public schools and statewide education policy.

New York schools are expected to receive state assessment results late this year — a delay that may change how schools decide which students need additional academic support.

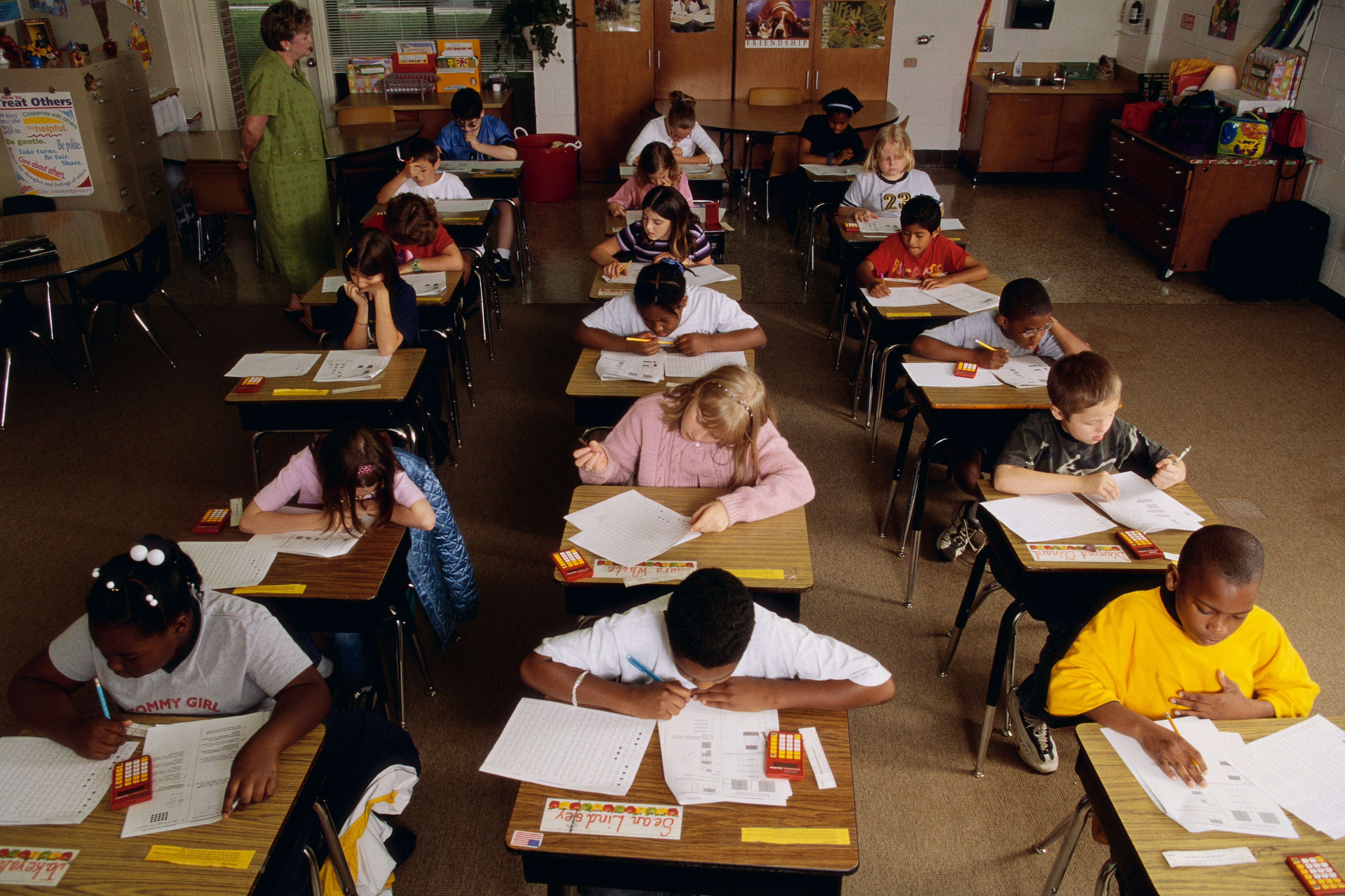

Each spring, schools across the state administer standardized exams in reading and math for third through eighth grade students. The results offer one look at how students are faring. For instance, they showed a steep decline in math scores in the city in 2022 as students faced severe pandemic disruptions, even as reading scores rose.

Under state regulations, schools must consider students who fall below certain scores for academic intervention services, but make final determinations based on a variety of factors and assessments.

The scores can also be one helpful measure for families and schools to identify ahead of the school year when students are struggling — arming parents with additional information as they may advocate for more resources. The scores can also help schools in making course and programming decisions.

This past spring, however, students took exams that followed new learning standards. The “Next Generation Learning Standards” were established after revisions from the controversial Common Core. Intended to clarify previously vague language, the new standards, for example, outlined specific theorems students had to learn in geometry, while the old standards stated only that students must be able to “prove theorems about triangles.”

State officials said more time is needed to analyze the results and develop “cut scores,” or thresholds for student proficiency, because it’s the first time the new standards were used.

The state department of education said results are expected to be released in the fall, but declined to provide a specific timeline. Last year, individual student scores were available to families and schools in August, though the broader, citywide figures weren’t publicly released until late September. (About 38% of third through eighth graders passed the 2022 math exams, while about half passed the reading tests.)

As a result of the expected delay, the state’s Board of Regents Monday adopted an amendment to state regulations allowing schools to bypass the required use of the scores to determine which students should be considered for academic interventions.

Those services are intended to help students who aren’t meeting the state’s learning standards with extra instructional time and support services.

Schools previously had to follow a two-step process to identify students in need of services. The first step involved considering all students who fell below an established threshold on the state reading or math tests. The second step required schools follow a locally-developed procedure to determine which students would receive academic intervention services.

Now, schools can opt out of the two-step process, instead relying solely on the locally-developed procedure.

According to state guidance, schools should consider multiple measures of student performance, including other assessments and psychoeducational evaluations — but must apply the same standards uniformly at each grade level.

It’s not the first time that schools will have flexibility to make such determinations without state assessment scores. The state previously gave such leeway to schools in the 2020-21 and 2021-22 school years, as the pandemic saw state testing canceled or disrupted, according to state regulations.

When reached for comment, DOE officials said they would review the amendment.

The amendment was adopted as an emergency rule, with a proposal for permanent adoption expected in November after a 60-day public comment period.

Additionally, when state assessment scores are released this fall, the new standards will once again make it difficult to compare results to prior years. Changes to the exams over the past decade have made it impossible to track trends over time, as officials have warned not to compare results to prior years when aspects of the tests are modified.

If screened admissions remain the same as last year, the test results should not affect fifth and eighth graders as they head into admissions season. In New York City, public middle and high schools that screen students from admission did not consider state test scores for this year’s rising sixth and ninth graders.

“While we do not anticipate major changes to school admissions, we are in the midst of engaging with schools and families and want to hear their thoughts about improvements to our process,” education department spokesperson Chyann Tull said in a statement.

Correction: This story initially said that test scores will not be considered for middle and high school admissions this year. The education department has not yet made its final determinations.

Julian Shen-Berro is a reporter covering New York City. Contact him at jshen-berro@chalkbeat.org.