Bach Tong, a 14-year-old from Vietnam, came to Philadelphia with his parents in 2008. The family sought the freedom and opportunity that they knew America could offer.

Two years earlier, Wei Chen, 16, and his family emigrated from Sichuan, China, with a similar goal. They, too, settled in Philadelphia.

Both of the boys enrolled in South Philadelphia High School, the neighborhood school for an eclectic and rapidly changing part of the city that had always attracted immigrants, most notably with Italians starting in the late 19th century. The two were among a large number of immigrants at the school, including those from West Africa and Central America.

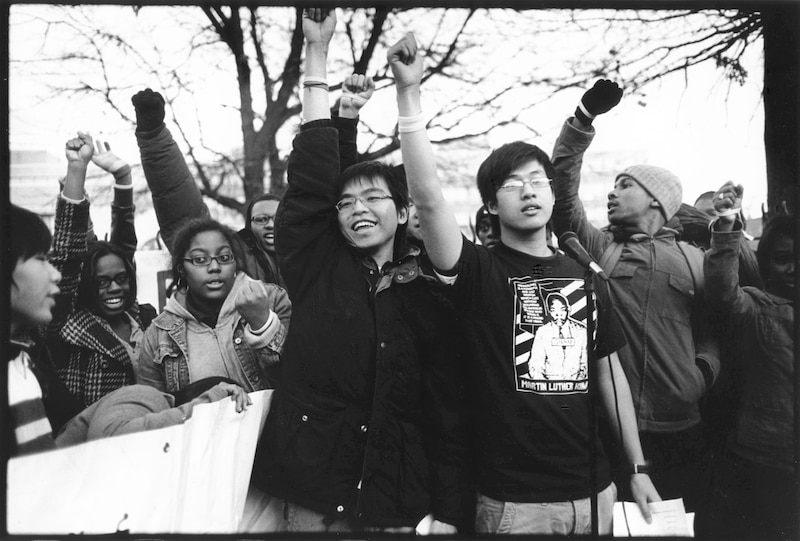

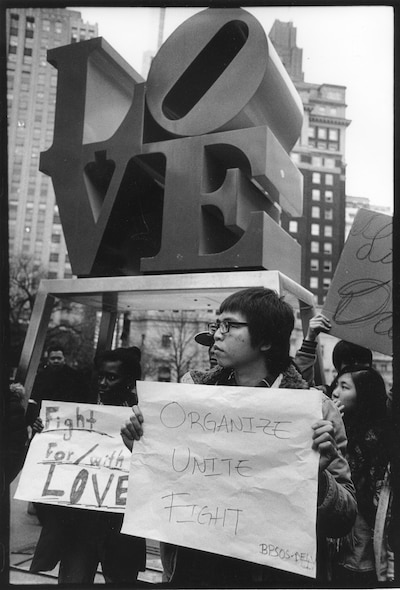

At South Philadelphia High, known as Southern, they entered a school community where Asian immigrants were harassed, bullied, and assaulted — behavior that school staff tolerated and sometimes abetted. On Dec. 3, 2009, more than two dozen Asian students were brutally attacked inside and outside the school building. Several were treated at hospitals for their injuries. After the attacks, Asian students organized an eight-day student boycott, forcing Philadelphia to confront the anti-Asian bias that permeated the city and its public school system.

The reckoning at Southern is now being revisited in the wake of the killings last month in Atlanta of six Asian women and two others in what is being investigated as a hate crime. On Thursday, Asian Americans United plans to hold a teach-in about organizing against anti-Asian violence.

“The issues the Atlanta murders raised are longstanding, part of the history of Asians in America since we’ve been here,” said Ellen Somekawa, who was the executive director of Asian Americans United at the time of the attacks at Southern and is now the CEO of Folk-Arts Cultural Treasures Charter School, or FACTS.

The school attacks led to the adoption of a districtwide anti-bullying policy, a landmark ruling in December 2010 by the U.S. Department of Justice, and a finding by the Pennsylvania Human Relations Commission that the Asian students’ rights had been violated.

“The federal consent decree against the school district was at the time a groundbreaking civil rights settlement and one of the largest in the country,” said Helen Gym, who was then a leader of Asians Americans United and Parents United for Public Schools. Gym is now an at-large member of the City Council.

The justice department found the district systematically violated the equal protection rights of Asian students “by remaining deliberately indifferent to known instances of severe and pervasive student-on-student harassment … based on their race, color and/or national origin.”

Gym says the settlement “is seen as a model for how to hold districts accountable for creating safer environments that still matters today.”

The events also forged a new generation of young immigrant community leaders, including Tong and Chen. Tong now works in Gym’s council office as a community liaison. Chen was appointed to Philadelphia’s Commission on Human Relations, won a prestigious national fellowship to work on promoting social change, and now works on civic engagement and voting in Philadelphia’s Asian community.

“What happened in my high school experience was a very important moment for me to change my mind about what new immigrants can do to change our lives, change our community,” Chen said.

Going to school in fear

When they arrived in this country, Tong and Chen landed in the peculiar institution of the American neighborhood urban high school, where the most vulnerable children often are concentrated together and then denied what they need to thrive. New immigrants from all over the world interact with students from marginalized groups who have their own history of oppression. At the time of the attacks, Southern had a student body of more than 800 students, which was two-thirds Black and nearly a quarter Asian, with a small but growing Latino population and a handful of white students.

Tong, now 27, remembers always being afraid — afraid to go to the lunchroom and afraid to move in the hallways between classes, for fear of taunts and attacks. And it wasn’t just students.

“When we went to the lunch room, there was staff who made fun of our accents,” he said. “The most heartbreaking and distraught reality was that when attacks took place, there seemed to be nothing done about it. We got no mental health services or support, there was nothing around healing, building a school community. We felt like we were not wanted by the rest of the school.”

That feeling was reinforced in myriad ways. The school isolated its sizable English as a second language program on the second floor of the building. Despite the diversity of the immigrant population, some administrators referred to the second floor as “the Asian floor,” Tong said. Students who weren’t in the program could be punished if they weren’t authorized to be on that floor for a class, a policy theoretically intended to keep students safe but one that built resentment among students.

About a month after he arrived, Chen recounted, he was trying to get a book out of his locker. Two students pointed at him, punched him and ran away. By the second semester of freshman year, “I was afraid to go to school.” He sometimes left home for school, but instead spent the day walking around the neighborhood.

By sophomore year, he said, “I find out more people had a similar struggle like me and that people were being bullied … but no one responded.” Sometimes, when a student tried to fight back, the administration “tried to suspend the victim.”

Before the attacks on Dec. 9, 2009, during his senior year, Chen reached out to community groups, including Asian Americans United, for help. On the day of the attacks, he took action. He called a reporter, and then he helped launch the boycott. It soon became national news.

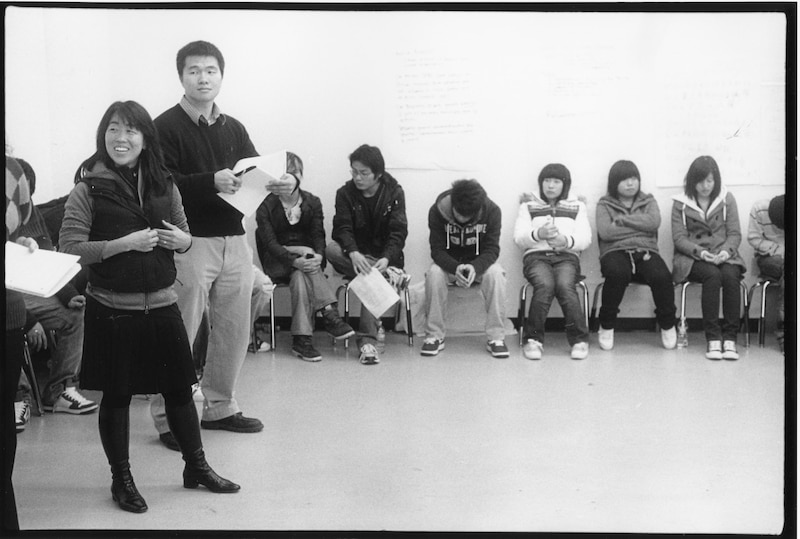

Both he and Tong were among those who organized testimony before the School Reform Commission, the state-dominated body that then governed the district, offering harrowing accounts about what happened that day: Asian students were attacked in the lunchroom as staff watched, a security guard allowed students to run through the second floor, and some staff members refused to help the injured. Some students, who were afraid to leave the building, were forced outside after school.

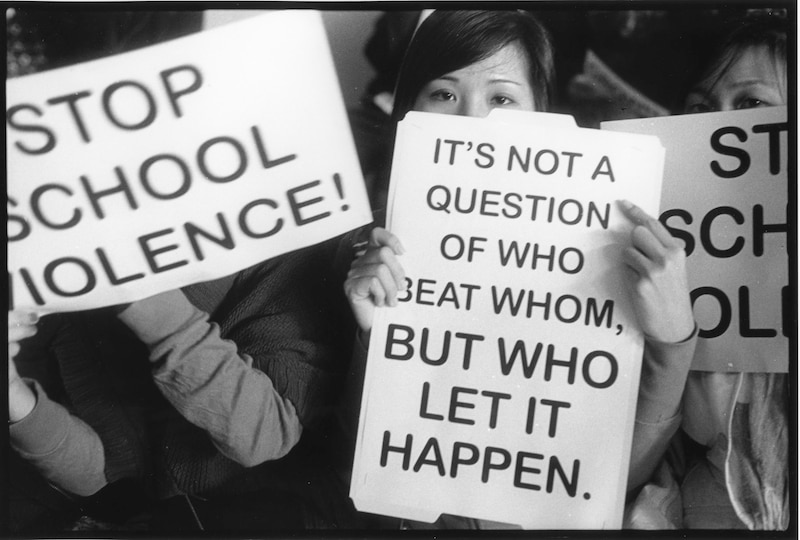

About 30 Asian students were attacked that day, mostly by a group of schoolmates who were Black, and some of the media coverage cast the incident as the result of tension between the two communities. But then and now, the students and community groups who advocated for them blamed school and district leadership, not other students, for what happened. In their protests, students carried signs saying, “It’s not a question of who beat whom, but who let it happen.”

“The important lessons to draw from what happened at South Philadelphia is that these acts of violence that are perpetrated by individual people are part of a larger structure of systemic racism and oppression,” said Somekawa. “You can’t look at them without looking at the broader issue of white supremacy. Look at how they continue to happen. It’s the failure of society to address issues of systematic racism.”

While the consent decree and the anti-bullying policy were positive outcomes, “less successful is the issue of a real rethinking of K-12 education,” said Somekawa. “You can’t have the story of the U.S. taught as if there is only one perspective.”

The superintendent at the time was Arlene Ackerman, who has since died. She initially refused to meet with the Asian student leaders until they went back to school, but they held out and she finally agreed. She also tried to minimize what happened, suggesting it was a result of gang activity and that the insults and attacks were mutual.

But at a Martin Luther King Jr. Day event a month later, she compared the experiences of the Asian students to her own when she was among Black students who desegregated schools in the South in the 1950’s.

“When we were allowed to go to school with white children, we were hated, and we were spat upon, we were attacked,” she said to an audience that included Black and Asian students from South Philadelphia appearing together. “I understand what that feels like.”

Both the settlement with the justice department and the anti-bullying policy requires school officials to record, investigate and act on all incidents of bullying and harassment reported by students, mete out discipline and offer “instruction and training to those whose actions were found to be inappropriate and/or hurtful.” It also says that the district is responsible for training staff “regarding all aspects of harassment and sex discrimination.”

For annual safe schools reports to the state, districts must account for incidents ranging from “minor altercations” to “terroristic threats” in all their schools. But between the 2008-09 school year and the 2017-18 school year, the Philadelphia school district reported 25 to 65 incidents of bullying and harassment a year – and fewer than 10 incidents of “racial/ethnic intimidation,” a separate category, according to the reports. In the 2018-19 school year, bullying incidents soared to 1,345, and there were 1,039 in the shortened 2019-20 school year.

Superintendent William Hite said that was due to an effort by the district to draw more attention to the policy and train staff members. The district also opened a hotline for students to call to report incidents.

“We had to dramatically increase awareness,” Hite said. “We felt the incidents were being under-reported.”

However, in those years there were no “ethnic/racial intimidation” incidents reported. Hite suggested that they were included in the other incidents of bullying because people weren’t aware of the different classification for them.

Gym, Somekawa, Tong, and Chen all said it was time to revisit the policy and take a deeper look into how effectively it is being enforced. Gym said “the policy only exists when people exercise it.”

“Any incident like [the Atlanta murders] should have the district dusting off its policies, reminding principals and school staff about them, reinvigorating training and strengthening protocols on the ground,” she said. “They should be asking school communities, most especially students and parents, if they know the protocol for reporting harassment, abuse or bullying to the school district, and if they do, whether they’ve gotten a response.”

Since the pandemic began, Chen said anti-Asian bias, especially against women, has increased markedly. “Currently our school district has not issued anything to talk about that,” he said. The district needs to “educate teachers, staff and students … racial justice has to be part of the curriculum.”

The requirements in the consent decree ran out in 2012, right around the time that deep cuts in state aid to schools devastated the district’s budget, decimating “non-essential” resources like counselors and training in cultural awareness for staff and students.

“Clearly this issue has not gone away,” Gym said. “It’s still extremely important for us not to assume that because a policy is in the books or we have a few more leaders, young people aren’t still experiencing bullying and harassment regardless of who they are.”

Earlier this month, Rita Chen, a seventh grader at Mayfair Elementary School in Northeast Philadelphia, told the Board of Education that she has been called racial slurs in school, a situation that has gotten worse during the pandemic.

“Several times school staff could have intervened,” she said. “People are looking for someone to blame.” Many students, she said, “are scared to go back” to in-person school.

In addition to enforcing the anti-bullying policy by investigating complaints, maintaining an online reporting system for incidents and offering training to staff, district spokeswoman Monica Lewis said that nearly half the schools use Positive Behavioral Supports and Interventions. PBIS is a program designed to improve overall school climate, in part, by nurturing and rewarding behaviors that “build relationships and a sense of belonging.” It also offers professional development to train staff on how to investigate and report bullying, harassment and discrimination.

The district also has set up a program called Relationships First that uses “restorative practices” in schools by helping students understand the effect of their behavior on others. More than 80 schools in the program start the day with community circles for restorative conversations; as schools get more practice with these, the conversations progress from airing issues to promoting healing to deciding on accountability for problematic behavior. A team of coaches help schools implement the program.

And as part of an approach to focus on social-emotional learning, this year the district introduced daily community meetings in all schools to help students “build skills like self-regulation, empathy and communication.” Since the pandemic, the district also has provided teachers with materials for facilitating conversations about racism against individuals of Asian and Pacific Island descent, Lewis said.

Advocates point out that since the policy was put in place, the district has fought lawsuits in which students sought damages for relentless bullying they endured in schools and settled one for $500,000. While the bullying and assaults occurred before the policy was put in place, the court battles occurred afterward.

Fighting for justice

After the attacks and the student-led boycott, the district administration moved to stabilize Southern, which had had five principals in the prior six years. They recruited Otis Hackney, who had been assistant principal at the school in the 2006-07 school year before leaving to lead a high school in the suburbs.

Hackney, now the city’s chief education officer, took over at Southern in 2010.

He made many changes. He started an Asian American history course. He allowed students to report incidents in their native language, which wasn’t permissible before. He also paid more attention to the behavior of staff members, oversaw training and held them accountable. “Adult behavior dictates student behavior,” he told Chalkbeat in an interview. “What we are doing as adults, and I include myself in that, we have to model behavior we want to see in students.”

He also apologized for his own verbal missteps and sought more training in cultural competencies. “We all need them, we all make mistakes in those spaces,” he said.

Hackney said he introduced a “growth mindset” to counteract the zero-sum attitude that permeated the school, that doing something for one group did not mean less for another group. And he made sure to understand cultural differences when he was sorting out misunderstandings among students.

For Tong, his experiences at Southern and the student boycott altered the course of his life. “It created a community of organizations and activists and it made me believe in organizing and fighting for systemic change,” he said. “It also made me realize how underfunded and understaffed our school was.”

He transferred for his junior and senior year, moving to Science Leadership Academy, a selective-admissions school with students from all over the city.

“It was a jarring discrepancy that was eye-opening for me,” said Tong, who later graduated from Bard College. His experiences in Philadelphia schools “put a fire in me to fight for a more just world.”

Chen, who was a senior when the boycott happened, wanted to repeat his senior year to improve his English and deepen his education, but was denied. He enrolled in Community College of Philadelphia and won a $50,000 fellowship from Peace First, given to young people for projects aiming to create a better world. Now 29, he does photography and works with Asians American United, focusing on civic engagement, specifically getting people in the community to vote.

His time at Southern “was a huge educational moment for me, for my political education,” he said. It changed his own expectations of what success in America would look like, from say owning a business, to something else, he said.

“I want to do something to change myself and change my community and continue fighting for justice.”