This story is featured in Chalkbeat’s 2022 Philadelphia Early Childhood Education Guide on efforts to improve outcomes for the city’s youngest learners. To keep up with early childhood education and Philadelphia’s public schools, sign up for our free weekly newsletter here.

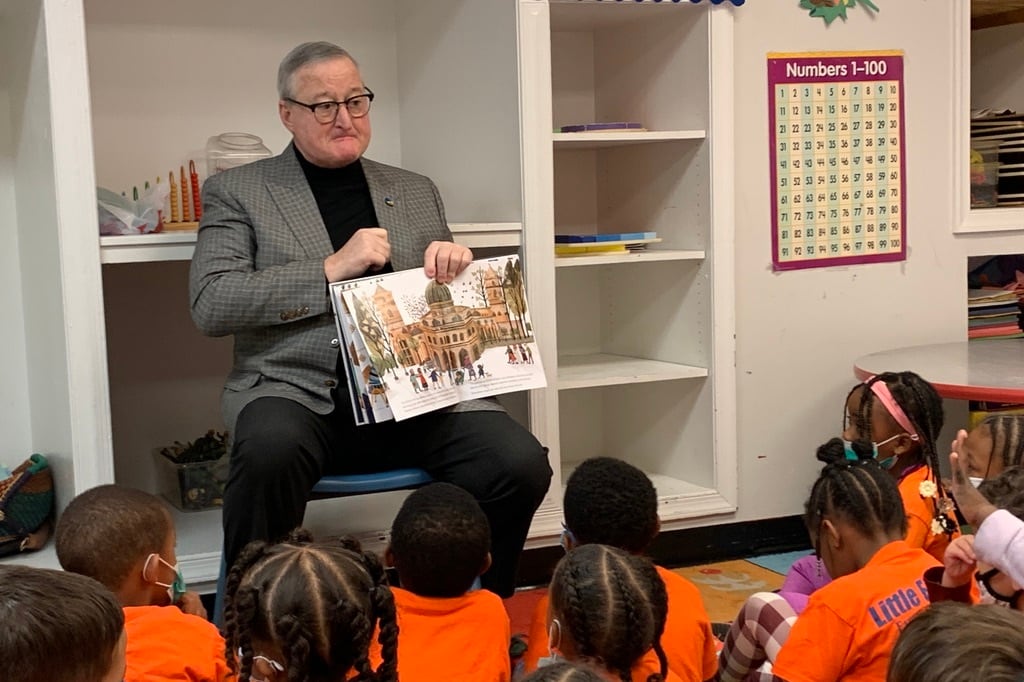

Mayor Jim Kenney had a question for the 30 or so four- and five-year-olds arrayed before him at the Little Einsteins child care center in Germantown just before Thanksgiving.

After reading to them from the book “Our Favorite Day of the Year,” about holidays, food was on the mayor’s mind.

“What do you like to put on top of your pie? I like vanilla ice cream,” he said.

“Pizza!” one little boy shouted.

“Pizza on top of your pie?” the mayor responded in mock disbelief. The little boy giggled.

Soon, it was a free-for-all. “French fries!” “Hot dogs!” “Nuggets!” children shouted.

“Now you’re being silly,” the mayor said, appearing to enjoy every moment as the children basked in the attention.

During November, Kenney visited several child care centers to highlight what he considers one of his biggest achievements as mayor: making affordable, high-quality early childhood education available to an additional 4,300 students through PHLPreK, an initiative that supplements state and federal programs including Pre-K Counts and Head Start.

The focus on prekindergarten is part of the city’s effort to ensure that all students can read on grade level by the end of third grade. This Read by 4th campaign began in 2015, and has brought together universities, foundations, businesses, and other institutions to emphasize literacy activities in everyday life as well as in the classroom.

As a target on the road to universal proficiency, the Philadelphia Board of Education has set a goal that 62% of third graders will be proficient readers by the 2025-26 school year. Yet while many systems have been put in place to help the city achieve its goal, the results so far have been mixed — at least as measured by standardized test scores.

Just 28.2% of Philadelphia third graders scored proficient or advanced in reading this year on the Pennsylvania System of School Assessment, or PSSA, according to a Chalkbeat analysis of the state test scores. That is not only a decline from pre-pandemic proficiency of 32.5% in 2019, but more than 10 percentage points below the goal set by the Board of Education for the 2021-22 school year for the district to be on track for its goal of 62%. (In 2020, the state did not administer the PSSA; in 2021, a relatively small share of students took the PSSA due to the pandemic, and officials have warned against comparing those scores to results from other years.)

Overall for grades 3-8, 34.7% of students scored proficient in reading on the PSSA in 2022. That’s below the interim target of 42.5% the district set for 2021-22 in order to stay on track to reach its goal of 65% proficiency by 2026.

Recently released scores from this year’s federally administered National Assessment of Educational Progress for fourth and eighth graders — known as “the nation’s report card” — revealed promising but also worrying signs for Philadelphia’s younger students when it comes to literacy.

While fourth graders’ NAEP reading scores dipped nationwide and in Pennsylvania, Philadelphia’s fourth grade reading scores did not change significantly from 2019, the last time the NAEP test was administered. At the same time, Philadelphia’s fourth graders scored significantly below the national average and the average for Pennsylvania. (NAEP is administered to a representative sample of students, not all of them.)

Despite worrying signs in the data, those working in the field also see encouraging signs.

Donna Cooper, executive director of the advocacy group Children First, called it “amazing” that Philadelphia’s fourth grade NAEP scores in reading “didn’t tank” for 2022 after all the pandemic-related disruptions.

And others point to the foundation for future success in literacy that Philadelphia has put in place recently through a diverse set of initiatives inside and outside schools. “We feel we’re in a much better place than we were seven years ago,” said Jenny Bogoni, executive director of the Read by 4th campaign.

Early literacy efforts focus on coaches and curriculum

The initiative started in the wake of research showing that students reap lifelong benefits if they are reading proficiently when they start fourth grade. A 2012 study by the Annie E. Casey Foundation, for example, found that students who do not reach this milestone are four times less likely to graduate high school on time than those who do.

Despite the added pre-K seats in Philadelphia over the last several years, inadequate availability may still be hindering efforts like those to improve early literacy.

About 12,000 children, or nearly half of those eligible for those seats based on family income, still don’t have access to affordable early childhood education, Cooper pointed out.

That could contribute to the reality that despite “tons of effort” after seven years “we’re not seeing movement” on the traditional measures of children’s literacy, she said.

Still, while the percentage of students reaching proficiency on the PSSA has not shown the progress people would like, the share of students scoring “below basic” (the lowest level) on the test did fall across various student subgroups from 2015 and 2019. For example, the percentage of Black male students scoring below basic on the English Language Arts test declined from 46.5% in 2015 to 41.5% in 2019, according to the district.

“We haven’t quite gotten to putting more in the proficient bucket, but we’re bringing up the bottom,” Bogoni said.

Starting in 2019, the district overhauled its early reading curriculum by hewing more closely to the science of reading, said Nyshawana Francis-Thompson, the district’s deputy chief of curriculum and instruction.

This shift in instruction seeks to couple comprehension skills — including vocabulary development, background knowledge, and verbal reasoning — with more explicit phonics instruction, decoding, and phonemic awareness, or the relationship between letters and sounds.

With the curricular shift, “We’re more focused on foundational skills,” said Malika Savoy-Brooks, the district’s chief academic support officer.

The district is also working with local colleges of education to make sure that teachers planning to work in the early grades get more rigorous training in reading instruction. And since 2015, early-grade teachers have received summer training in best practices for teaching reading.

Beyond that fundamental shift in core instruction, the district has also hired literacy coaches recently to work in many schools. Officials have also sought to raise awareness among parents about the importance of exposing them to books from a very early age.

Outside of school, the Read by 4th campaign has enlisted the help of “reading captains.” These are community residents who conduct literacy activities in the neighborhood at libraries, schools, parks and other settings.

Diane Castelbuono, the district’s director of early childhood education, said there is “a small army of reading captains out there engaging friends and neighbors in how to raise a reader, and how families can access the resources they need.”

Separately, the district is working with book publishers and funders to obtain more diverse books, and enhance classroom libraries to make sure most of the books and teaching materials are more culturally responsive to the children in the classroom, who are overwhelmingly Black and brown.

Francis-Thompson said the district is drawing on materials and philosophy from Dr. Gholdy Muhammed, an associate professor at Georgia State University who emphasizes the importance of cultural affirmation and appropriate reading materials to children’s development of literacy skills.

“Significant work has been done making sure there are books in children’s homes, making sure the distribution of children’s books is culturally responsive and in different languages,” Castelbuono said.

While curriculum is important, so is making sure that the teachers of early learners also focus on children’s social and emotional needs, said LaTanya Miller, executive director of the district’s office of academic supports who works on adaptive curriculum for students with disabilities.

And with respect to English language learners, who make up 12% of the district’s students, the district has also gradually shifted its approach to stress that speaking and understanding a language other than English is an asset, not a liability.

Over the past several years, the district has invested in modernizing kindergarten through third grade classrooms to include centers devoted to reading, writing, and LEGOs.

And officials are ramping up other initiatives, including playful learning, in which opportunities for reading and conversation are present in places all around the city, including parks, laundromats, and buses.

The ultimate goal of all these efforts, Francis-Thompson said, is to prepare students to be critical of the world around them and “not just a passive consumer” of information. Beyond just teaching skills, creating literate students is about “accepting them and embracing all that they are in a learning environment,” she said.

As with many other education initiatives, the pandemic has disrupted efforts to improve early literacy. Bogoni said almost two full years of remote learning has taken its toll. But she stressed that the city is now in a better position to make badly needed progress.

“We were feeling we were on the cusp of making good progress as the pandemic hit,” she said. “Now the task is to double down. The foundations are in place that should allow us to move forward in this space of urgency.”

Dale Mezzacappa is a senior writer for Chalkbeat Philadelphia, where she covers K-12 schools and early childhood education in Philadelphia. Contact Dale at dmezzacappa@chalkbeat.org.