Chicago plans on opening a handful of schools in the next several years. But for whom?

Chicago Public Schools faces a critical decline in enrollment and is closing or phasing out four more schools on the city’s South Side as a result.

Yet the district just unveiled a new $1 billion capital plan that adds schools: an open-enrollment high school on the Near West Side and an elementary school in the Belmont Cragin community on the Northwest Side. That’s in addition to repurposing two old buildings to open classical schools in Bronzeville on the Near South Side and West Eldson on the Southwest Side.

CPS is soliciting feedback about the plan this Thursday ahead of next week’s board of education vote, but community organizers say the proposal shows a bias toward investments in or near high-growth, gentrifying areas of the city. Some complain the new schools will siphon enrollment and resources from current neighborhood options, and worry the schools are an election-year ploy that will exacerbate or enable gentrification. Others contend that the district’s spending still prioritizes white and mixed communities near downtown and on the North Side as opposed to majority black and Latino communities on the South and West sides.

Despite the criticism, and despite declines in city population and enrollment, CPS said it is taking a neighborhood-by-neighborhood approach to to creating new schools and academic opportunities. In a statement to Chalkbeat Chicago, CPS defended its decision to open new schools, despite enrollment declines, by citing community demand. And CPS CEO Janice Jackson told a room of business and nonprofit executives at the City Club of Chicago on Monday, “we can’t do great work without investing” — and not just in school staff, but in buildings themselves.

At a budget hearing later in the day, Chicago Board of Education President Frank Clark stressed the money was being allocated “with a great deal of focus on local schools that in the past had legitimate reason to feel that they were not prioritized as they should (be).”

The problem, still, is fewer and fewer families are enrolling their students at CPS.

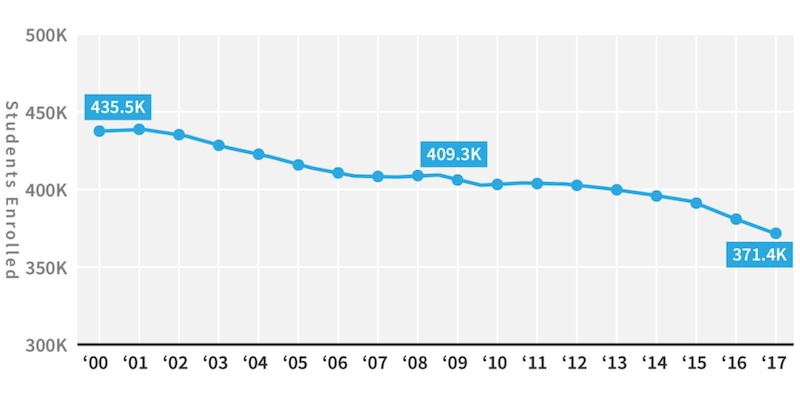

The roughly 371,000 students enrolled at CPS this year is a 15 percent decrease compared with the year 2000, when enrollment topped 435,000, according to CPS data. And there’s no sign the numbers will trend upward soon: The district projects about 20,000 fewer students to enroll in the next three years. The trends mirror population drops in Chicago, which has about 182,000 fewer residents than it did 18 years ago, according to Census data. More than 220,000 black residents have left since the year 2000.

One expert on neighborhood change in Chicago, Alden Loury of the Metropolitan Planning Council, said building new schools shouldn’t be part of a broad policy given the city’s population declines. However, he said new schools may make sense in certain areas.

“You may see pockets within the city where there’s a very clear difference happening,” he said.

Demographer Rob Paral, who publishes Chicago demographic data on his website, said while the city’s population might be down, some parts of the city that have grown, especially areas that are gentrifying and former white ethnic enclaves transformed by Latinos and immigrants.

“Chicago has got these microclimates when it comes to neighborhood change,” Paral said.

You’ll see what he’s saying in Belmont Cragin, a community just west of one of Chicago’s most popular gentrifying communities, where the population has ballooned as the overall city population has dropped.

A new elementary school for Belmont Cragin

Belmont Cragin is a quiet, working-class neighborhood full of single-family brick bungalows and two-flat apartments. Taquerias, Mexican boutiques, hair salons and auto bodies dominate commercial corridors that used to serve more Polish residents, who are concentrated on the northern end of the community. Since 1990, Belmont Cragin’s population has increased 40 percent to 80,000 and changed from two-thirds white to 80 percent Latino. Paral said Latinos have moved from communities like Logan Square to the east, where gentrification pushed them out, and replaced aging white populations. Latinos have similarly transformed former enclaves for European immigrants on the Southwest Side, like West Eldson and Gage Park.

CPS said in its statement that community groups and leaders in Belmont Cragin advocated for the elementary school, and that CPS “shares these communities’ vision of expanding high-quality educational opportunities to children of all backgrounds.”

CPS wouldn’t say who in the Belmont Cragin community had asked for a new school. It wasn’t Rosa Reyes or Mariana Reyes (no relation). They said their children’s school, Burbank Elementary, is losing students and needing improvements to its roof, heating and cooling systems. The district labels Burbank, like most schools in Belmont Cragin, as efficiently using its space and not yet suffering from under-enrollment — yet. Still, its student body is shrinking. Latino enrollment at CPS seems to be falling, too. Experts note that immigrants are coming to the city at much lower rates than in the past when they offset black population loss, and that birth rates have declined across the board.

The mothers said CPS allowed a Noble Charter Network to open in 2014 that exacerbated enrollment declines at Steinmetz High School, and that the same happened to Burbank in 2013, when an UNO charter elementary opened a few blocks west of the school.

Steadily losing students costs Burbank funding, doled out per-pupil. That’s why they the parents don’t support CPS’ new school proposal.

“It will be taking from the local schools,” Rosa Reyes said.

A push for a Near West Side high school

Drive west from Chicago’s central business district and you’ll pass through the Near West Side, one of the city’s 77 official community areas. However, those official boundaries also contain a racially and economically diverse mix of neighborhoods. East of Ashland, you’ll see the West Loop, home to mostly white and affluent residents, pricy condos, trendy restaurants, and a booming business community that includes corporate headquarters for Google and McDonalds.

But west of Ashland, as you approach the United Center where the Chicago Bulls play, you’ll find more low-income residents, public housing, and African-American residents. Like Belmont Cragin, the Near West Side has witnessed immense population growth in recent decades. White people have flocked to the area, especially the affluent West Loop, while the black population has plummeted. In 1990, about 66 percent of Near West Side residents were black and 19 percent were white. Nearly 20,000 new residents have moved in since then. Today, the Near West Side is 30 percent black and 42 percent white. An analysis by the Metropolitan Planning Council found that most African-Americans leaving Chicago are under 25, and low-income. Alden Loury, the council’s research director, said the city is struggling to retain young black people who might eventually establish families, and that many black Chicagoans have left seeking better job markets, more affordable housing, and higher quality schools.

CPS hasn’t announced where on the Near West Side it will put its proposed $70 million high school – but the community groups calling loudest for it are pro-business groups and neighborhood organizations led by mostly white professionals. The community group Connecting4Communities and the West Loop business organization the West Central Association have advocated for a new high school and see the mayor’s proposal as responsive to the growing community.

“Most of the high schools that people are comfortable sending their children to, the good ones, are selective enrollment,” said Executive Director Dennis O’Neill of Connecting4Communities.

He said that parents whose children don’t test into those schools—Jones College Prep, Whitney M. Young Academic Center, and Walter Payton College Prep —lack an acceptable option.

“Our neighborhood school, Wells, which is nowhere near our neighborhood, is so under-enrolled, and is not [a school] that people feel comfortable sending their children to,” he said. “When people see a school is so woefully under-enrolled, they just don’t have confidence in it.”

Wells Community Academy High School, which sits near the intersection of Ashland and Chicago avenues, also is mostly black and Latino, and mostly low income.

But O’Neill emphasized that high school request isn’t an effort to exclude any groups. He said the groups have a proposal for a new high school that draws on eight feeder schools, including a school serving a public housing development, to ensure the student body reflects the diversity of Chicago.

Loury of the planning council said it makes sense that as the Near West Side grows there’s a desire to satisfy that growing population. However, he found the idea of low enrollment at a predominately black and Latino school amid a boom in white population to be problematic. Parents might avoid sending their children to certain schools for various reasons, but a new building nearby furthers disinvestment in schools struggling to fill seats.

“It’s a pretty classic story in terms of Chicago and the struggles of integration and segregation,” he said.

A classical debate in Bronzeville

When it comes to CPS’ new school plans, line items don’t always mean new buildings, as evidenced by the two classical schools opening in existing structures in West Eldson on the Southwest Side and in Bronzeville on the South Side.

Bronzeville Classical will open this fall as a citywide elementary selective enrollment school. Classical schools offer a rigorous liberal-arts curriculum to students who must test in. Last year, more than 1,000 students who qualified were turned away for lack of space, according to CPS, which is spending $40 million to expand three existing classical programs elsewhere.

“The district is meeting a growing demand for classical programs by establishing programs in parts of the city that do not have classical schools, like Bronzeville – making this high-quality programming more accessible to students in historically underserved neighborhoods,” the CPS statement read.

Alderman Pat Dowell, whose ward the school is opening in, supports the new Bronzeville school.

“It provides another quality educational option for families in Bronzeville and other nearby communities,” Dowell wrote in a statement she emailed to Chalkbeat Chicago. “No longer will children from near south neighborhoods seeking a classical school education have to travel to the far southside, westside or northside for enrollment.”

However, some South Side residents see the classical school as problematic.

Natasha Erskine lives in Washington Heights on the Far South Side, but is Local School Council member at King College Preparatory High School in the Kenwood community near Bronzeville. She has a daughter enrolled at King, a selective enrollment high school. Before that, her daughter was in a gifted program at a nearby elementary school. Erskine supports neighborhood schools, but struggled finding schools that offered the kind of field trips and world language instruction many selective enrollment schools offer.

“I see the disparity, because it’s one we participate in it whether I like it or not,” she said.

Bronzeville is a culturally rich neighborhood known as Chicago’s “Black Metropolis,” where black migrants from the South forged a vibrant community during the Great Migration, building their own banks, businesses and cultural institutions.

And it retains a resilient core of committed black residents, but has suffered some decline and lost population like other black neighborhoods. The community area that contains Bronzeville and Douglas has lost about half of its black population since 1990.

But Bronzeville is adjacent to the gentrified South Loop, which is grown increasingly white in recent years. And it’s a short drive from Woodlawn, where the Obama Presidential Center is slated to be built. Paral, like other observers, predicts the Bronzeville is one of the areas between the South Loop and the Obama Library that will be further gentrified in coming years.

Jitu Brown, a longtime Chicago education organizer and community leader who heads the Journey for Justice Alliance, believes that the investments are an attempt to attract more white families to areas at a time when low-income people and African-Americans are being priced out and leaving the city. Brown added that creating more selective-enrollment schools is a different type of segregation: “You’re segregating talent.”

On Thursday, the district will solicit feedback about the spending plan via simultaneous public hearings at three different sites, Malcolm X College, Kennedy-King College, and Truman College. Here are the details.