When a small group of central office staff met earlier this year at Chicago Public Schools headquarters to discuss a grant, the conversation went from how the district could support students’ social and emotional development to a bigger discussion about the world children are growing up in. CPS CEO Janice Jackson said the talks inside district headquarters at 42 W. Madison St. soon “blossomed into a full blown commitment around race and equity.”

On Wednesday, the Chicago Board of Education is expected to vote on CPS’ 2018-19 budget, which lists a new four-person Office of Equity as a $1 million line item. The board also plans to vote on a proposed revision to its student code of conduct to help address racial disparities in suspensions.

Related: With Earth, Wind and Fire tune, Chicago’s first chief equity officer announces new job

Equity officers are a small but growing cadre of school administrators working on diversity and inclusion. Districts in Los Angeles and New York don’t yet have a cabinet-level official who reports directly to the schools chief. But smaller urban districts like Jefferson County Public Schools, in Kentucky, and the Oakland Unified School District, have been doing the work for years.

“This is a good start, we’re excited about the direction we’re going in,” Jackson said.

In a racially equitable school, all students would get what they need to be successful, and race wouldn’t predict any child’s success or outcome. But how does a chief equity officer go about digging out so many deep-rooted problems at CPS?

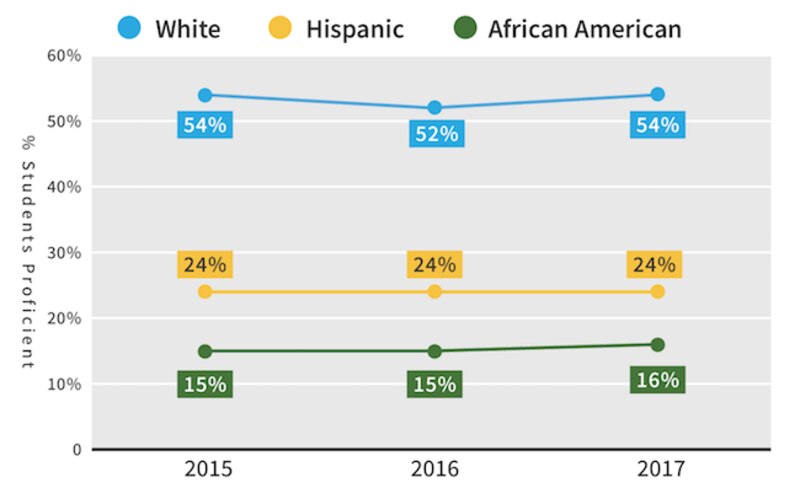

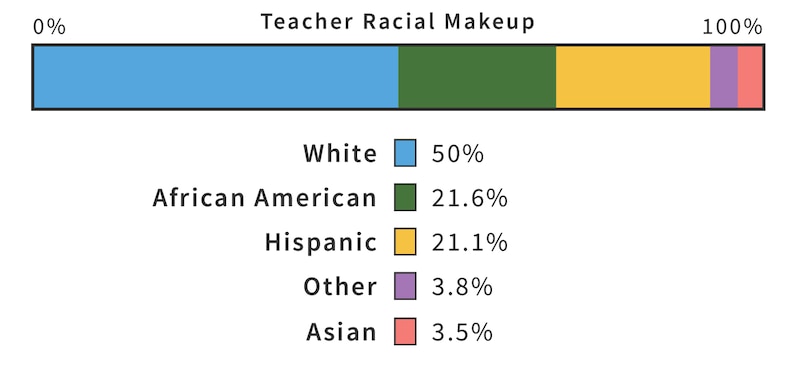

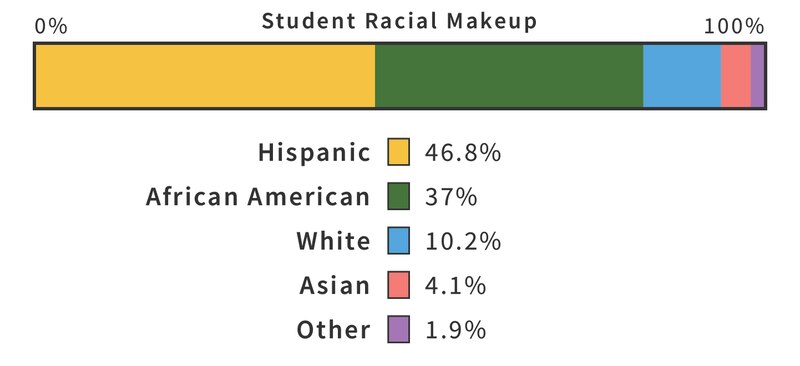

In Chicago, one of America’s most diverse — and segregated — cities, few institutions illustrate racial inequity like the public school system. About 90 percent of CPS students are of color, but half of all teachers are white. White students, most of whom live on the North Side, comprise just 10 percent of students but are nearly all clustered at top rated schools (Level 1+ and Level 1). Black and Latino students, who are concentrated on the city’s South and West sides, also trail their white peers when it comes to test scores and college readiness.

The consequences of racial inequity in schools can follow students their entire lives. Jackson knows that all too well. She grew up on the South Side of Chicago, graduated from public schools, and returned as a teacher and principal.

Now chief of the district, Jackson said the equity chief’s primary focus in year one would be bridging gaps in test scores between black and Latino students and their white peers. “All tides are rising,” she said, citing academic growth at the district, “but the achievement gap still exists.” And while she said it’s too early to pinpoint every equity goal and standard, Jackson detailed some initiatives the new official would work on, starting with diversifying CPS’ workforce, ensuring resources are distributed equitably across the district, and supporting CPS efforts to award more contracts to minority- and woman-owned businesses.

To better understand what a chief equity office could look like, Chalkbeat interviewed school equity experts in several areas. While no school district has eradicated the problem, a savvy equity chief is starting to make a major difference in some cities.

Lessons from the Bluegrass State

John Marshall grew up in a family of educators and attended failing schools in Louisville, Kentucky. After a high school suspension he felt was unfair, he vowed at a school disciplinary hearing to one day change the school system from the inside. Today, he’s the chief equity officer at Jefferson County Schools, which encompasses Louisville and is Kentucky’s largest district with more than 100,000 students, about 46 percent white and 37 percent African-American.

He said that a $3.6 million budget his office assesses the practices, policies, and behaviors of the school system, with a focus on access to academic programs, teacher recruitment, discipline and student achievement. He has spearheaded the creation of an equity institute to train employees and provide professional development. Last year, the school board approved creating a school for men of color with lessons taught “from an Afrocentric lens,” rather than the Eurocentric instruction prevalent at many American schools.

Marshall has some tips for CPS CEO Jackson as she seeks a chief equity officer: choose somebody who is organized, data-driven, research focused, and who understands the business of public education. That means not just hiring a bureaucrat, business person, or political operative — but snagging a candidate with experience teaching at and leading schools.

It’s also important to hire a person who can build bridges between the administration and community groups and enlist help in building momentum for racial equity work. And, he said, it wouldn’t hurt to have candidates who have experience in the same school district they hope to improve.

“Do you need them to be from Chi-Town? Not really, but it’s helped me being from Kentucky,” he said.

One of the most vital qualities a chief equity officer should have, Marshall said, is a deep understanding of race and history. Tackling racial inequity means wrestling with the legacies of colonialism, slavery, and racial discrimination.

“What [equity officers] have to do is look at the system as not broken,” Marshall said, “but as doing what it’s created to do.”

Year one: a scorecard

When Marshall was hired in 2012, he said he focused on creating an equity scorecard loaded with critical data that grades the district via four metrics: literacy, college-and-career readiness, school climate and culture, and discipline. He said the data has helped focus the community conversation and strengthened efforts to improve outcomes for certain students. For example: The district saw some increases in the number of low-income students considered to be college and career ready between 2013 and 2016.

The data-laden equity scorecard has been a powerful guide in other ways, too.

For instance, Marshall said that his office recognized that students of color were being suspended at a disproportionately high rate. He worked with community groups to come up with a remedy, redefining the categories of conduct that were generating suspensions, namely, disruptive behavior. “This subjective infraction was being given to black males of color in alarming and disproportionate ways,” he said.

The disparities in discipline he mentioned are also a problem in Chicago. While the district has revised its suspensions policy and seen a steep decline since 2012, black boys are still the most likely to be suspended.

But none of this will work if the people who run schools can’t speak honestly about race. Lee Teitel runs a program at Harvard’s Graduate School of Education that sends graduate students into schools to coach teachers and administrators on issues around race and equity. The students report back that it’s challenging, Teitel said. The problem is that it’s hard for some people to confront their personal issues with race — and comprehend the impact racism has across institutions like public schools. That’s the sort of education an equity chief must bring to school communities, networks, and central offices.

“You’ve got to change attitudes and beliefs, and you also have to give people the tools to do that, because dismantling racism in the schools is just as hard as it is dismantling it in the larger society,” Teitel said.

Listening tours

Christopher Chatmon, deputy chief of equity for the Oakland Unified School District, has his own advice for Chicago’s equity officer. Do a listening tour that spans anywhere from six months to a year, and interview students, parents, teachers, principals, central office staff, school board members, and community organizations.

That’s what Chatmon did after his office opened in 2016. It grew out of the district’s Office of African-American Male Achievement, which he helped found in 2010. Chatmon previously had worked as a principal at an alternative school in San Francisco and served executive director of Urban Services at the Oakland YMCA. Oakland Unified serves about 50,000 students and is 46 percent Latino, 24 percent black, 13 percent Asian, and 10 percent white.

“As we began to go deep into the work, we realized the evolution of that work would have more legs and tentacles,” Chatmon said. “We began to see that not only do we need targeted strategies for black boys as way to elevate access and performance, we also could benefit from having differentiated and targeted strategies for Latinos, Latinas, indigenous students, Asian and Pacific Islander students.”

In his first year, he drafted an equity policy that declared the district’s commitment to identifying and eliminating racial bias, and outlined ways to reach that goal. Now, his office is laying the groundwork for the plan and thinking through teaching and learning, professional development and curriculum (“the content is still extraordinarily Eurocentric,” he said), teacher recruitment and retention, parent engagement, budgeting, and social-emotional supports for children.

He has about 20 staff, including researchers and data analysts. In a district budget of about $780 million, his office has a $2.1 million slice.

The office spends money on outreach to parents, students, other community engagement events, and training teachers. The office also works on “narrative change,” sharing the stories of diverse students via newsletter, and informing people about accomplishments made by the office.

It’s a subtle way to counteract negative narratives about students of color, LGBTQ students and other marginalized people, Chatmon said. It also lets the public know the district’s values and keeps people abreast of its work.

“Otherwise,” he said, “you can be doing good work but it gets either suppressed or it doesn’t get lifted up.”

“CPS is stepping up”

Chicago’s equity officer won’t have an easy job. This new hire will step into several heated debates around racial equity, especially how CPS plans to spend $1 billion on improving school facilities, adding annexes, and shiny new buildings. He or she will also have to address teacher pipeline issues: The racial makeup of CPS’ teacher workforce doesn’t reflect the student population or that of the city as a whole.

A recent WBEZ analysis found CPS’ proposed capital budget invests disproportionately more in buildings serving significant white populations and schools on the north side. And Chalkbeat Chicago reported last week that the proposal shows a skew toward investments in and near high-growth, gentrifying areas of the city. Critics are inflamed by what they say is the lack of an intelligent, fair or transparent process for prioritizing community needs.

At capital budget hearings last week, residents had mixed feelings about how CPS is allocating resources. Some applauded the district, while others cried out for more help.

Jackson said the district already has laid some equity groundwork, such as the Great Expectations Mentor Program, which grooms African-American men and Latinos interested in senior leadership roles at CPS. She also mentioned investments in under-enrolled schools, which tend to be in black communities that have been losing population.

“CPS is stepping up and and saying this is important, and while we have always prioritized equity, it’s important to have a cabinet level official [focused on equity],” Jackson said.

Even if Chicago’s chief equity officer transforms schools, public education is only one expression of racial inequity. Marshall, in Kentucky, emphasized that fixing a school system doesn’t change discrimination in banking, criminal justice, or housing. That doesn’t mean equity chiefs should throw their hands up in resignation. On the contrary, he said they should sit on anti-gun violence panels, address laws that perpetuate mass incarceration, and tie these issues back to schools, especially the school-to-prison pipeline.

“A school system is one link in the chain of change,” he said.