Vocational education used to mean machine shops and sewing classes, programs aimed at students who weren’t headed for college. But career education has changed to fit the tastes of today’s students and the needs of the 21st-century job market, and now encompasses courses ranging from game design and aviation to architecture and digital media.

And Chicago schools are expanding their array of career-prep courses in hopes of enticing students back to languishing neighborhood high schools.

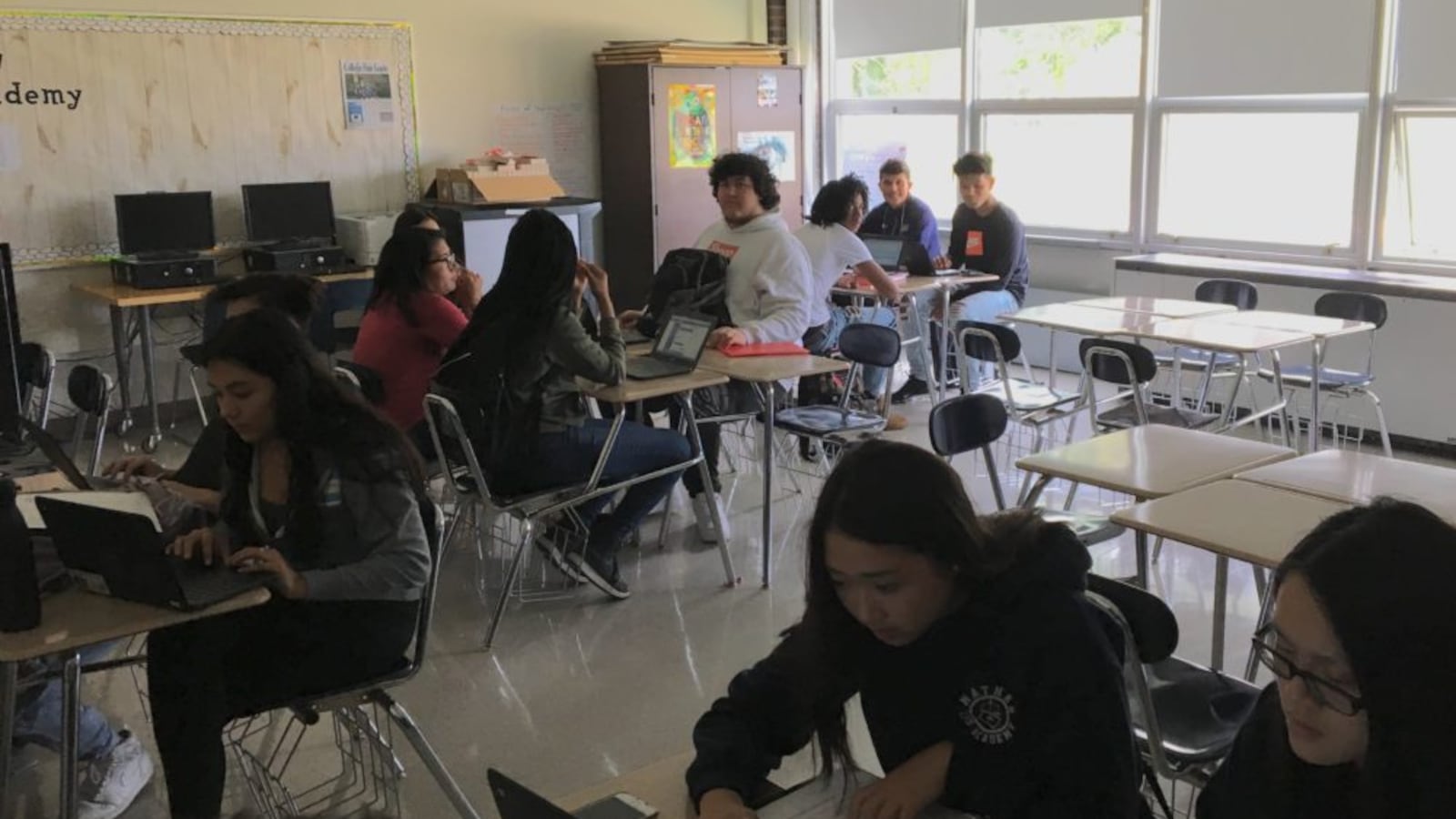

A tour of Mather High on Wednesday demonstrated how Chicago schools are viewing career education differently. It’s a means of both attracting students with training in popular subjects and using those practical classes to teach fundamental concepts — all very much aimed at sending some career-track students to college.

For example, Mather’s pre-law curriculum includes a criminology course where students learn about psychology, as well as a mock-trial element where they learn classical principles of rhetoric and argument. The pre-law program also dedicates time to helping its students submit college applications — hardly the focus of traditional trade-school curricula.

At Mather in West Ridge, second-year Principal Peter Auffant reversed a five-year slide in enrollment after expanding career-related classes. About a third of Mather’s 1,500 students are enrolled in one of its four career-education tracks, including a brand-new pre-engineering curriculum. A digital media track is slated to begin next fall. Besides more than three dozen classes, career-related offerings also include internships, such as stint working in city council members’ offices or at downtown law firms.

“CTE allows us to provide very unique programming that students can’t get anywhere else,” Auffant said, referring to the commonly used shorthand for career technical education. “We leverage that to create stable enrollments.”

Mather senior William Doan is a case study. Three years ago, the West Ridge resident was looking at high schools outside his neighborhood — selective-enrollment schools as well as those offering the rigorous, college-preparatory International Baccalaureate curriculum, but ultimate chose to stay close to home because Mather’s pre-law program aligned with his interest in law enforcement.

“It kind of just drew me in,” Doan said. “You get a taste for the law and how it really is in the real world.”

Doan’s experience reflects a trend that’s shaping curricular decisions in Chicago and around the country. Congress this summer approved $1.1 billion to expand career education. Such offerings are among Chicago Public Schools’ most popular, according to a report released last month by the University of Chicago Consortium on School Research and the Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago.

Some of those programs focus on traditional vocational education, such as the building trades program at Prosser High in Belmont Cragin that Mayor Rahm Emanuel announced this month would be funded with a $12 million investment. Others like those at Mather include non-traditional offerings, described as “21st century CTE” by Jarrod Nagurka. He is advocacy and public affairs manager for the Alexandria, Virginia-based Association for Career & Technical Education, which sponsored Wednesday’s school tour.

Nearly every Chicago high school has at least one career offering, though access to the most popular programs varies across the city, as does the breadth of the programming at each school. One factor among mid-sized schools such as Mather is the administrative burden of supporting extensive career programming alongside other elective programs such as International Baccalaureate.

“To do both (IB and career education) really well you have to be larger,” Auffant said.

So Mather is pursuing a hybrid strategy that uses career-education classes to teach college-prep concepts. Teachers use real-world vocational settings to explore the academic concepts that undergird them.

“The foundation of curriculum design is backward design,” said Sarah Rudofsky, the school district’s manager of curriculum and instruction for CTE. That means consulting with industry partners about the skills graduates need, then building curricula to suit. In a pre-law course, for example, those core skills are destined to overlap with traditional college-prep coursework, but geared to a practical application.

“It’s important to us to change the conversation from ‘CTE is for students who don’t want to go to college’ to ‘This program is for any young person who wants to have some employability skills before they graduate from high school’ — applied math, applied science and applied literacy,” Rudofsky said.