Steven McDuell had been looking forward to the big game since his freshman year.

Like many seniors at Detroit Delta Preparatory Academy for Social Justice, the school’s star running back saw the homecoming game as more than the high point of the football season. It would be a moment that he and his classmates — a tight-knit community of students who had bonded since the ninth grade — would remember for the rest of their lives.

But that moment never came. On Wednesday, Sept. 26, the charter school’s board held a meeting with a single item on the agenda: the closure of Delta Prep. Parents, students, and teachers piled into the auditorium to demand that their school be spared, but their outpouring of tears and grief was not enough.

Two days before the homecoming game, the board voted to shut the school down — effective immediately.

When the meeting was over, dazed students spilled onto the sidewalk by the front door, many of them with tears still visible on their cheeks. A couple of students kicked down one of dozens of yard signs stuck in the grass by the sidewalk:

“Detroit Delta Preparatory Academy,” they read. “Now Enrolling 9th-12th grades.”

The lurching suddenness of the closure stunned educators and parents, triggering a chorus of outrage that would spread across the city. But, in truth, there was nothing sudden about what happened at Delta Prep.

A review of hundreds of pages of documents, and interviews with key leaders involved in the school since its creation, show that the forces arrayed against every school in Detroit had pushed Delta Prep’s chances of survival to nothing within a year of its opening, if not before.

The dense thicket of recruitment signs told only the final, desperate chapter of a failure foretold — from Delta Prep’s optimistic start as the brainchild of some of Detroit’s most driven women, through its zig-zagging quest to get permission to open, to its very existence in a city that already had too many schools for its struggling student population.

Efforts to regulate Michigan’s charter school market were repeatedly foiled by deep-pocketed advocates including U.S. Education Secretary Betsy DeVos, and Delta Prep students are still paying a price they can hardly afford.

But as they mourned their school, the students weren’t thinking about education policy. All they felt was sadness.

“All I know is Delta,” McDuell said. “For them to sit there and tell us it’s closing, it’s heartbreaking.”

✴ ✴ ✴

Delta Prep’s sudden demise added to a two-decade drumbeat of school closures that has left Detroit’s education landscape in turmoil, and has forced thousands of students to endure the serious social and academic consequences of unnecessarily changing schools.

Those consequences are especially pronounced in Detroit, where students’ new schools are likely no better than their old ones.

Charter school advocates see closures as an unfortunate but necessary part of a bargain that should benefit students: Schools get more autonomy to operate, but if they fall short of their goals, they have to close.

Some cities and states have tried to limit closures by giving charter schools more support and resources. Others require public hearings and community input long before a school can be shuttered.

But efforts to regulate charter schools in Michigan have run into fierce political headwinds, in large part because of DeVos and her family, who have used their considerable fortune to support a free market education system that allows charter schools to open wherever they believe they’ll succeed.

DeVos and her allies have been so successful in blocking efforts to regulate charter schools in Michigan that when the founders of Delta Prep began looking for permission to open back in 2012, they had no shortage of options. They could pick from roughly eight colleges and school districts that were empowered to authorize charter schools, some of which would provide more oversight than others. When it finally opened in 2014, Delta Prep was one of more than a dozen schools that opened in Detroit and began competing for the same students.

A 2016 law put some limits on which organizations can approve new charters in Detroit, but there are still no rules about where or how many schools can open. There are also no rules that prohibit schools from starting the school year on September 4, and closing three weeks later.

Teachers, students and parents were stunned that this was allowed to happen.

“I felt insulted,” said Gwendolyn Hunter, whose son was a senior at Delta Prep. “They could have told us they didn’t have any money. Why are you going to open a school for three weeks if it’s going to close?”

But Lou Glazer, president of a Michigan think tank focused on education and economic development, says state laws make this kind of instability all but inevitable.

“It’s just what happens when you have lots of people acting in their own best interest, and no one is thinking about the system,” Glazer said.

He learned this lesson the hard way, during a seven year stint as an influential backer of charter schools. Beginning in 2009, his organization helped to steer millions of dollars to new high schools that would form an “alternative educational system” in Detroit.

Among the beneficiaries of Glazer’s support: the women with a vision for a social justice themed school that would become Delta Prep.

✴ ✴ ✴

Edythe Friley had spent a lifetime around Detroit’s schools, graduating from the city’s elite Cass Technical High School and going on to work for three decades as a high school social studies teacher and as an administrator.

She’d seen the city’s education crisis unfold, watching as a generation of students left school without the skills they needed to succeed, and as countless efforts to turn things around fell short.

So she decided to do so something about it.

Friley wasn’t the only retired educator in the Detroit chapter of Delta Sigma Theta, the largest sorority of black women in the country. She and her sorority sisters often volunteered in schools, following the sorority’s legacy of public service, but now they agreed that they needed to do more. They would try to open a school.

“We were much too young and too able and everything else to just mentor,” she said.

The path from imagining a school to starting one would have been more challenging almost anywhere besides Detroit. In many cities, including Washington, D.C. and Newark, a central authority would have scrutinized Friley’s proposal, the proposed school’s finances, and the need for a new school before deciding whether it could open. In most of the U.S. states that allow charter schools, the proposal could have run into laws that put a cap on new schools.

But even though Michigan made it easy to open charter schools, Delta Prep’s path to launch was rocky.

Friley says her sorority sisters were divided over whether to support the school proposal. Some thought the group shouldn’t be involved in running schools, while others opposed charter schools, which have drained students and resources from the city’s main district. But after being assured that the school would have a social justice focus, the women agreed in a split vote to lend their organization’s name to a new high school.

The hurdles didn’t end there. The group struggled to find a management company to take on the school’s day-to-day operations, and the first authorizer it approached, Eastern Michigan University, shot down its proposal in the first round.

Then Glazer got involved, and things changed. His group was running a project called Michigan Future Schools, which had received millions of dollars from big-name Detroit-area philanthropies — Skillman, Kellogg, Kresge, McGregor — to kick-start high schools in the city. (Chalkbeat Detroit is funded by these philanthropies. Read our code of ethics here.)

It gave $800,000 of that money to Delta Prep.

Glazer was impressed by the proposed school’s social justice focus, he says now, and the involvement of a powerful sorority didn’t hurt. Detroit’s Delta chapter counts local judges, doctors, and educators among its members.

“There’s no question that the fact that it was going to be a Delta-sponsored school was one of the attributes in our choosing them,” Glazer said.

Glazer recruited EQUITY Education, a nonprofit school management company that had helped open other philanthropy-backed Detroit high schools, to sign on. EQUITY agreed, and in the fall of 2013 the company submitted a school proposal to Ferris State University, promising to launch “one of the most innovative and relevant charter high schools in Detroit.”

From the start, the school’s social justice theme was central to its appeal. There wasn’t another Detroit school with “social justice” in its name, and everyone involved says it made the school sound like the kind of project that could succeed in Detroit.

Glazer sent staff to New York City to visit the Bushwick School for Social Justice, a small charter school that has won high marks for pushing students to attend college and for a project-based curriculum that encouraged students to tackle social issues affecting their neighborhoods.

“We came as people from the City of Detroit to try to correct the ills of public education for kids who really had no other place to go,” Friley said. “We started out as a social justice school to right some of the wrongs of what we’d been seeing as educators.”

The theme was convincing to officials at Ferris State, a public college in western Michigan that has overseen more than a dozen charter schools in Detroit since 1998, including at least five that closed. Ferris signed off on the Delta Prep proposal, clearing the way for the school to bring in state funds.

Now it was up to the school’s founders to fill their first class — and they were certain that the social justice theme would attract students. EQUITY estimated that Delta Prep would enroll 200 students in the first year, and 500 students within five years.

But when Delta Prep opened in September of 2014, just 52 students enrolled in a former district elementary school that once held more than 1,600.

✴ ✴ ✴

Delta Prep opened during a period of educational chaos that was extreme even by Detroit’s standards. Within two years, a barrage of charter school closings in the city would send 7,000 students — roughly 6 percent of the city’s student population — in search of somewhere else to pursue their education, exacerbating Detroit’s struggle to help students stay stable in one school.

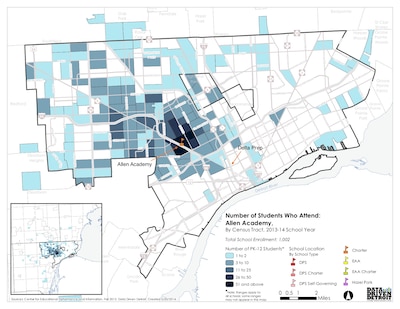

Among the casualties were Plymouth Educational Center Preparatory High School and Allen Academy, two of the city’s largest and lowest-performing charter high schools. Allen’s enrollment hovered around 1,000 students, but fewer than a dozen members of each senior class typically completed a year of college within one year of graduation.

After news of the closures broke, Delta Prep officials moved quickly to recruit the displaced students. Delta had fallen badly short of its enrollment projections for the first year, and in any case, providing a place for those students seemed to fit with the school’s mission.

“We guaranteed that if they came to Delta Prep, we’d correct the wrong of their school closing and keep them together,” Friley said.

Delta Prep was far from the only school wooing the displaced students. Michigan school funding is based almost entirely on the number of students enrolled, and at the time, each additional student brought in about $7,000 per year. Schools’ financial survival often depends on luring new students.

Delta Prep’s leaders were thrilled when their recruiting efforts paid off, swelling enrollment to 322 in its second year.

But such rapid expansion raised red flags with national charter school experts who learned about Delta Prep from Chalkbeat. They pointed out that some cities, such as New Orleans, use a common enrollment system designed to limit any one school from being flooded with a disproportionate number of high-need students. (Other cities also have a closer balance between school seats and students, reducing the likelihood of having many empty spots to fill in the first place.)

The extra work that comes with additional students — hiring more teachers, expanding food and transportation services — could put an unsustainable strain on a fledgling school, said Robin Lake, director of the Center for Reinventing Public Education, a think tank that studies and generally supports charter schools.

“Schools that really are putting student welfare first will pay attention to the impact of a rapid expansion of student population, and will pay attention to the price that other kids will pay if a lot of other kids are coming in with challenges that the school can’t handle,” Lake said.

Tyler Shaw, chief of staff for EQUITY Education, said school administrators believed they were ready for the new students, despite the obstacles those students faced and the well-documented challenges of finding qualified teachers in Detroit.

“We were in a facility that could handle taking that many students,” she said. “We could staff the building appropriately for that many students.”

✴ ✴ ✴

Finding enough teachers for every student was not the same as meeting their needs.

Many new schools in Detroit start with the dream of defying the odds stacked against the students — the poverty, housing instability, poisonous politics, and unfettered competition that have kept the nation’s most successful charter operators away from the city.

Delta Prep was no exception, but within three years of its opening, it was falling badly short of the vision laid out in its application to Ferris.

Delta officials had promised that “90 percent of students will attend every class, on time, every day.” But in the school’s third year, just 20 percent of students came to class with any regularity.

Officials said they would boost student achievement by borrowing from the playbook of a New York-based education nonprofit. Their goal: “85% of students will demonstrate competency in all core subjects via exit tests.”

But within three years, not a single Delta Prep 11th-grader was deemed proficient in math, compared with 13.2 percent in Detroit’s troubled main district. Just 10 percent of 11th-graders posted passing scores in SAT English, compared with 37 percent in the district.

Delta Prep had promised that “100% of graduates will be accepted to college.” But in 2016, the only year the state recorded graduate data for Delta Prep, just over half of the school’s graduates enrolled in college. Just six students — 10 percent of that first graduating class — went on to complete a year’s worth of college credits within a year of graduating.

If the data was concerning, the situation inside the school was even more dire. When Brandi North was hired as principal in 2017, the first thing she did was hire security. The sprawling school was built during an era when Detroit couldn’t find enough classroom space for all of its students, but now it sat mostly unused, and students tended to disappear into vacant classrooms. Teacher-student relations were antagonistic. North said her assistant principal’s hand was broken during an encounter with a student, and that she regularly contacted the police about student behavior.

The year before she arrived — and the year after the influx of students from recently closed schools — Delta Prep had slapped more than half of its students with out-of-school suspensions, resulting in nearly 1,000 missed days of school.

“In 15 years of education, it was the most stressful position I’ve ever had,” North said. “I worked in south central Los Angeles, and Delta was still my most stressful situation.”

North started at the school in March 2017, after the previous principal resigned and an interim principal decided not to take the job. She says she found tutors for students, brought consistency to a patchwork curriculum, even drove to students’ houses on test day to make sure they took Michigan’s standardized exam. But she left that June following disagreement with the management company that she declined to discuss.

She was not the only administrator unable to cut it at the school. Within a few years of its hopeful start, Delta Prep had become another Detroit school desperate to find the rare principal capable of quarterbacking a long-shot school turnaround. It had five principals in less than five years of operation.

Susan Therriault, a researcher at the American Institutes for Research who focuses on turnarounds, said the nation’s most troubled schools often struggle to keep principals, even though experts view them as pivotal.

Without stability in the principal’s office, “you’re just reacting constantly to these fires, and you’re not able to put structures in place to actually support struggling students,” she said. “Thats hard in any school, and then you have a school that grew very, very rapidly.”

Indeed, after reading and hearing about Delta Prep, Therriault wondered how the school lasted as long as it did: “Why did it get this far?” she asked. “The whole point of [creating a charter school] is to be creating incentives for students to enroll, designing programs to attract students.”

✴ ✴ ✴

In Detroit’s crowded education landscape, Delta Prep kept falling short of its 400-student target, creating a financial situation so bleak that students lacked textbooks and other basic supplies.

When officials from Ferris State came to check in on the school, they noted that only one-third of its budget was spent on instruction, while far too much went to the management company and other operating costs. Delta Prep’s reserve fund, set aside to protect the school against unforeseen problems, dipped to $217 in 2017-18.

“$217 is a rounding error,” said Michael Addonizio, a professor of education at Wayne State University who specializes in finance. “That’s pretty close to the bone.”

Making matters worse, Ferris State officials raised concerns that the board wasn’t keeping a close eye on the budget.

“The Board of Directors need to ask the right questions so they get accurate and complete answers, especially in … financial matters,” the officials wrote.

Looking back on the situation, Friley, the board president, said she believes Delta Prep was set up to fail financially. She pointed to the state’s school funding formula, which experts say does not recognize the additional challenges facing Delta Prep and other schools where the vast majority of students come from poor families. And she blamed the school’s low instructional spending on the management company, which she said did not do enough to recruit students.

“When you look at the charter movement, the amounts of money that are taken off the top are not filtering down to the kids,” she said.

Shaw, EQUITY’s chief of staff, said that her organization donated tens of thousands of dollars to Delta Prep over the years, and that the company’s nonprofit status “speaks for itself.” In any case, she said, the company increased its spending on instruction after Ferris State raised concerns about its budget.

But last June, as Delta Prep approached the deadline for submitting its annual financial plan, it was clear to anyone paying attention that the school was in crisis.

A few months earlier, state officials put Delta Prep on the watchlist of Michigan’s lowest performing schools, pointing to its academic results, low attendance, and problems with student discipline. If the state didn’t close Delta Prep, there was a real chance that Ferris State might. The school’s charter contract was set to expire the following June, and after it had repeatedly missed its targets for enrollment and academic performance, the outlook didn’t look good. Test scores showed little sign of budging, and most of the students the previous year had been seniors, meaning they would have to find additional new students just to break even.

As tensions rose, the already frayed relationship between the board and EQUITY Education snapped. EQUITY had opened a different high school, infuriating the Delta board, and now the management company announced that it planned to pull out entirely within a year.

“EQUITY had not been fully able to implement our model for educational services,” Shaw explained. “The school board and sorority had a very specific vision.”

At other schools, the circumstances might have justified shutting down in June. Across Michigan, several schools shut down every year in less dramatic fashion, shutting their doors when classes break for the summer.

But the founders of Delta Prep clung to their dream. They were determined to open their doors for another year in September.

“We had hope that … that we maybe could survive,” Friley said.

But no one was prepared for how few students showed up to Delta Prep after Labor Day.

Friley said she hoped that 350 students would enroll this fall and EQUITY’s budget documents anticipated that 264 students would enroll.

Instead, the first three weeks of the school year saw an average daily attendance of just 180 students — a decline of more than 30 percent from the previous year.

Enrollment fluctuations are common in Detroit, where one in four students change schools every year. Many schools find it hard to predict how many students will show up on the first Wednesday of October, when the official student count determines the bulk of a school’s state funding.

The blow was too much for Delta Prep. On Sept. 26, 22 days after the school year began, the board voted to shut the school down.

EQUITY’s president, Renee Burgess, had pleaded with the board to keep the doors open. She arrived at the board meeting that day armed with a shaved-down budget — including a $73,000 pay cut for the company — that she said would allow the school to remain open through the end of the year.

Observers and experts say Delta Prep officials could have done more to anticipate the worst, but in truth the school had operated near the financial brink for most of its existence.

“I was not surprised at all,” North, the former principal said of the closure. “What did shock me, was that they allowed it to open for three weeks. Because it was in dire straits before that.”

More than a month after the closure, Friley told Chalkbeat that the board did students a favor by closing the school, given its financial and academic problems.

“You just look at the landscape, and you say, like a doctor, just do no harm,” she said.

It’s impossible to identify a single point of no return for Delta Prep: Was it the moment that the board’s relationship with its management company became fractious? Or the moment school leaders, desperate to boost enrollment, filled their building with high schoolers whose needs they were unprepared to address? Or was it even earlier, when Michigan’s most respected philanthropies used their money and connections to give a flimsy school proposal a second chance?

The school’s story is littered with good intentions, and more than one protagonist has come to view the school’s very existence as a mistake, one that they hope will serve as a warning flare to a city and a nation still struggling to stabilize their schools and, by extension, their future.

“There’s no question that I was way over-optimistic about their ability to recruit kids,” Glazer said. “I should have recommended pulling the plug. In retrospect, the school should not have opened.”

Ron Rizzo, president of the office of charter schools at Ferris State University, said his organization would be “looking into” improving enrollment predictions because of the Delta Prep closure.

“If we don’t learn from this one, shame on us,” he said.

Asked whether Delta Prep should have opened in the first place, Friley says she wished she started smaller, perhaps steering away from high schools, which are more expensive to operate than primary schools and enroll students who have already had many years to fall behind.

“No,” she said. “Our best thing would have been to look at a K-8 situation. Or a K-2.”

Charter school researchers who heard the Delta Prep story said the uncertainty and tumult that plagued Delta Prep is an indictment of charter school oversight in Michigan.

“It just sounds like there’s a missing management and oversight piece,” Therriault said. She added: “The pain for families and kids is real.”

That pain was impossible to ignore as students stood up at the board meeting on Sept. 26 to protest the closing of their school. They talked about what it felt like to be forced out of a school where many of the seniors had begun their high school careers. And they expressed fury at the timing of the decision, which came so suddenly that when the meeting let out at noon, many students waited for hours until their parents, caught unaware, could leave work to pick them up.

In the days after the closure, the homecoming football game that McDuell and his classmates had been looking forward to was cancelled. But the consultants hired to help students find new schools sought to ease the emotional blow by saving the homecoming dance. The result was a cross between a typical high school dance, a farewell party, and an apology. There was a DJ, a photo booth, and a sheet cake with the words “Well Wishes and We Love You All” written in the red and white color scheme that the school shared with the Delta Sigma Theta sorority.

McDuell was there, wearing jeans and a white T-shirt instead of his usual football jersey and trying to keep his feelings at bay.

“I really didn’t try to think about the school actually closing till the end,” he recalled. “Then I felt kind of down because my school was closing. I had been there since the ninth grade.”

The following week, most of McDuell’s classmates transferred to other schools run by EQUITY, according to Rajeshri Gandhi Bhatia, CEO of School Smarts, a consulting firm hired to help with the transfer process. Some transferred to schools in Detroit’s main district and in the suburbs.

Between eight and 10 students are still unaccounted for, Bhatia said this week.

McDuell transferred along with the rest of the football team to Old Redford Academy, a charter school 10 miles from Delta Prep, where they finished their season in different jerseys.

The commute was longer, but the transition went pretty well on the whole, McDuell said. He’s trying to think less about Delta Prep and more about college.

“Right now I’m just trying to get my education,” he said. “It’s my senior year, so I’m trying to make it count.”