A new state vision for Tennessee’s lowest-performing schools would give schools making gains more freedom to see through their own turnaround efforts and provide greater state oversight in schools that aren’t improving enough. But schools that show little or no progress could still be taken over by the state.

State leaders say that means they can concentrate more money on schools with greater needs and give local districts more say in improving schools that are closer to escaping the state’s list of “priority schools,” which score in the bottom 5% on annual state tests.

The Tennessee Department of Education’s draft plan for its 82 priority schools was presented at a community meeting Tuesday evening in Memphis. Department staff also publicly unveiled a proposal to transition the 30 schools already taken over by the state out of the Achievement School District in two years, which Chalkbeat reported Monday.

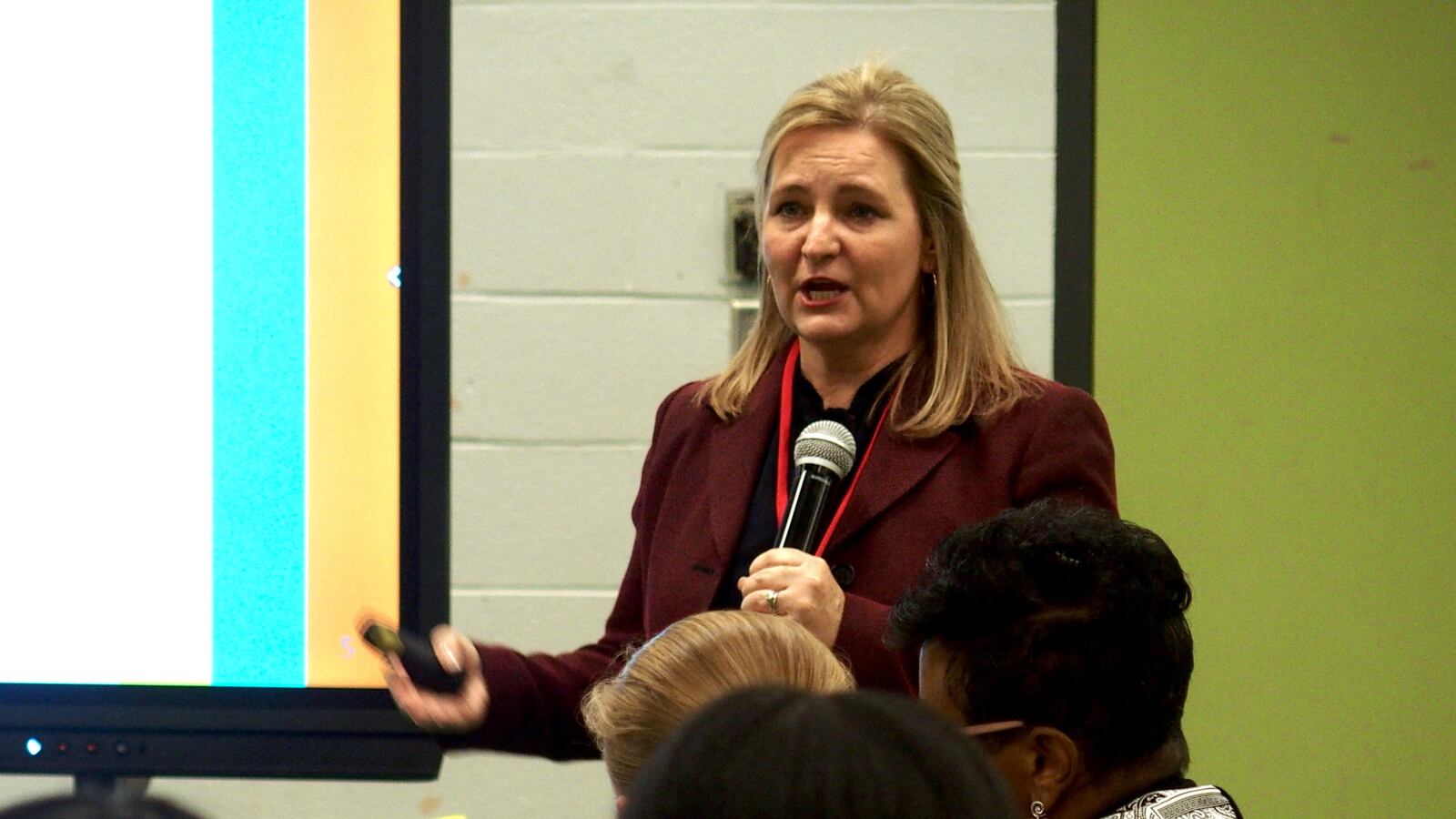

The proposal is the first under Tennessee Education Commissioner Penny Schwinn to lay out how the state thinks its lowest performing schools should better serve students.

Eve Carney, the state’s chief districts and schools officer, said the state would consider more than just test scores and academic growth when placing schools on three levels of intervention, or “tiers.” The state would also take into consideration a school’s student discipline rates, how often students are absent from school, and how many students are prepared for college or a job.

“Just to be frank, we will be in your schools, we will be in your business,” Carney said. “But this to me feels like we are trying really hard to give you what you need so your school doesn’t go into the ASD.”

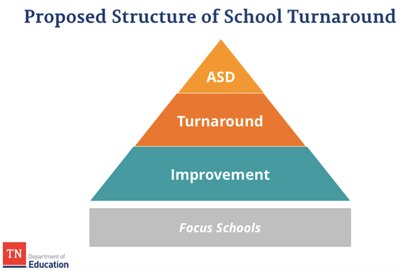

Below is a brief description of each of the department’s proposed tiers, which would go into effect during the 2021-22 school year:

- Tier I, Improvement: Each school would receive $50,000 in state support, which districts could pool together to fund identified needs. The state deems schools in this category to have effective improvement plans in place and simply need more time. The schools would remain in district control, but the state would evaluate their curriculums and programs, and require regular reports on progress. State officials estimated about half of priority schools would fit into this category.

- Tier II, Turnaround: Each school would receive $300,000 to $500,000 in state money and have a substantially longer list of state requirements including regular teacher observations, a community advisory board at each school, and overhauling student discipline. The state would also require a school resource officer and a nurse at each school.

- Tier III, ASD: This level is reserved for the state’s most extreme action of taking over a school through the Achievement School District. Department staff promised to return in the coming months to gather feedback on how the district will change, but gave few specifics Tuesday.

When schools are not on the state’s priority list, but its English language learners, students of color, or students with disabilities test among the bottom 5% statewide, the state will require improvement plans and monitor it for up to three years before designating it a priority school. The state calls these “focus schools.”

The state’s forthcoming hire for a “turnaround superintendent” would oversee schools in the last two levels of intervention, rather than focus solely on the Achievement School District.

“I thought it was really important to have a leader who was invested in getting it right in tier two, not just in the Achievement School District,” Carney told the audience. “So if that step becomes necessary, that leader has been in those schools, has already engaged those communities, so there’s more of a connection.”

The meeting attracted about 100 people and was held at Trezevant High, which sits in the Memphis neighborhood that has experienced the most state takeovers since 2012.

Memphis is home to 40 priority schools: 22 in Shelby County Schools and 18 in the state-run Achievement School District. The next priority list is expected to be released in 2021. Under the state’s proposal, the state would place all priority schools in one of the tiers effective during the 2021-22 school year.

Some of those priority schools are already in a district-run school improvement program, known as the Innovation Zone or iZone, and they could continue in the program under the state’s proposal. The iZone has shown more academic gains than the state’s turnaround district, which researchers said posted about the same scores as schools that received no additional help.

“I’m encouraged that some of the supports they talked about are things we are already doing,” said Angela Brown, an instructional leadership director for the iZone.

Some educators at the meeting asked for more state training or resources to address chronic absenteeism and student discipline — especially since those measures could be a deciding factor in the state’s assessment of schools.

“What I would really want to see funded at my school is an incentive program to deter negative attendance or poor behavior and academics,” said Willie Johnson, a family engagement specialist at Southwind High School.

Others hoped the state would put more money on the front end before schools need highly prescriptive state involvement or eliminate the Achievement School District altogether.

“They didn’t do our children right,” said Rebecca Murray, whose grandchildren has attended state-run schools. “I don’t see the improvement. They’re still at the bottom of the barrel.”

Commissioner Schwinn was not at Tuesday’s meeting, but is scheduled to be in Memphis on Wednesday for a meeting with Shelby County Schools’ top leader, Superintendent Joris Ray, to discuss the proposal.

“With the legislative season here, the commissioner attending the events wasn’t possible,” Carney told Chalkbeat.

The department vowed to schedule more community meetings to gather feedback on the draft as state legislators weigh options in the upcoming session in Nashville — a marked departure from the previous administration. Memphians have clamored for more say in how the state approaches low-performing schools, and some were still cautious Tuesday.

“I’m trying to wait and see instead of assuming anything,” said Shelby County Schools board member Stephanie Love, whose children were zoned to three schools the state district took over in its early years. “I hope the people at the table have the heart to say we messed up. We need to make sure we don’t continue the same mistakes.”

State officials said this time will be different.

“We want schools to be rooted in their community,” said Robert Lundin, the state’s assistant commissioner of school models and programs. “Nobody at my office, myself included, ever presumes that somebody in a bureaucratic office in Nashville knows better what’s needed for schools than people in their community.”

Reporter Caroline Bauman contributed to this story.