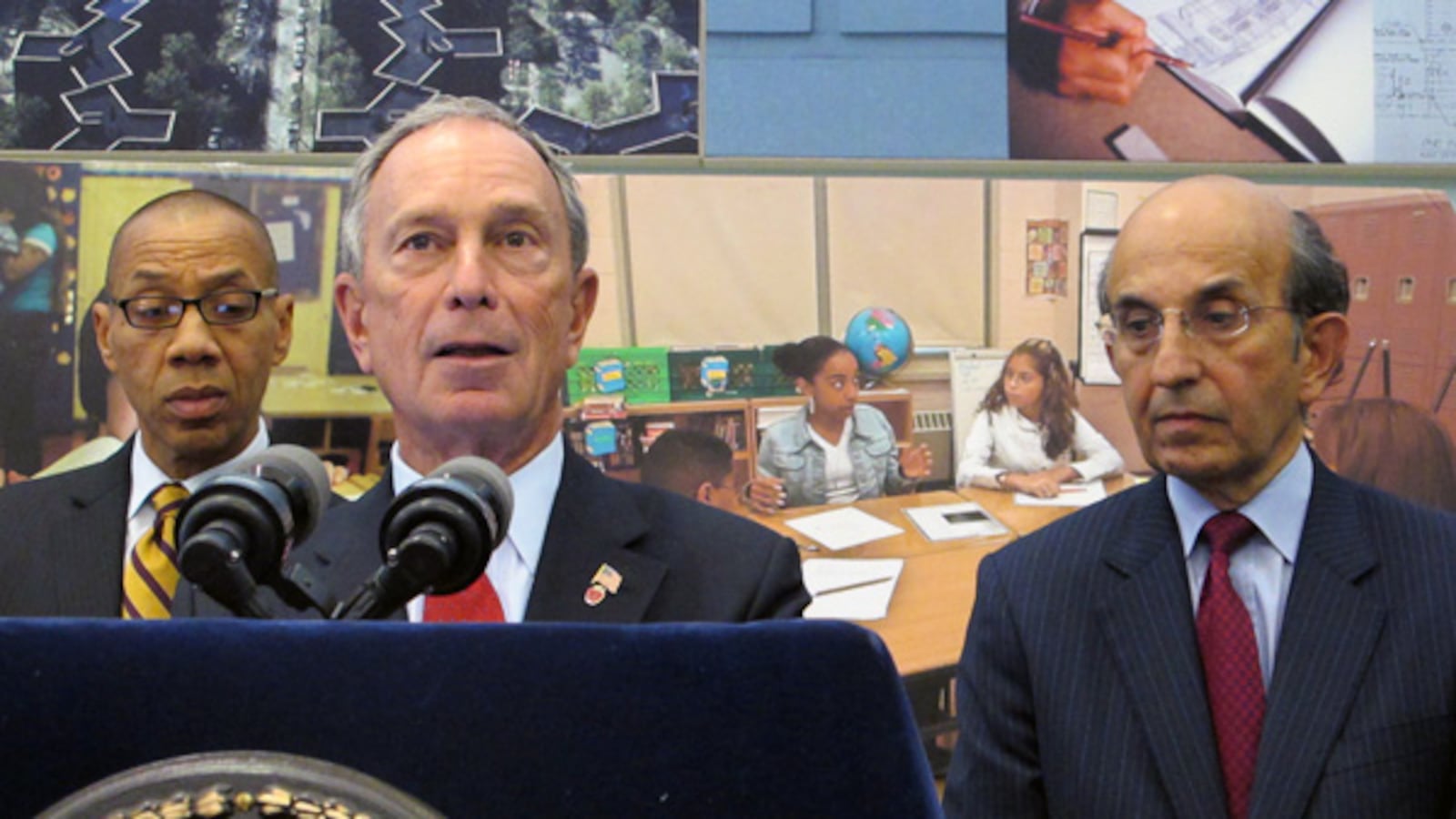

As mayor of New York City, Michael Bloomberg was one of the most powerful people in American education.

For more than a decade, he effectively controlled the country’s largest school system — a power he had pushed the state legislature to grant him in 2002 — and he took full advantage of it, closing schools, expanding charters, and agreeing to large teachers raises (before alienating many teachers and their union). Now, Bloomberg is running for president on his education record, painting a rosy picture of his tenure.

“Through the collective efforts of New York’s city leaders, teachers, principals, parents and of course students, Mike took a dysfunctional, underperforming system and turned it into an extraordinary success story using innovations based on data — expanding those that worked and ending those that didn’t,” said Marshall Cohen, a Bloomberg campaign spokesperson. (Bloomberg Philanthropies is a funder of Chalkbeat.)

Bloomberg’s policies have been extensively studied by researchers, and Chalkbeat reviewed dozens of these studies to understand more fully his administration’s impact. Some specific policies, like high school closures, were vindicated by subsequent research. But others, like grade retention and merit pay for teachers, didn’t work.

And today, New York City schools are wrestling with how to unwind deeply entrenched patterns of segregation that persisted through the Bloomberg era.

James Kemple, the executive director of the Research Alliance for New York City Schools, said Bloomberg’s 12-year tenure was defined by steady improvements across most metrics.

“Every ship was rising,” he said, but noted that disparities across critical demographic and economic groups remained.

Jennifer Jennings, a Princeton University professor, who has studied and critiqued many Bloomberg-era policies, said some of them were successful, but that others came with serious downsides.

“The school report cards and the incessant focus on increasing state test scores by any means necessary,” she said, “it created a focus on a small set of outcomes.”

Here’s a deeper look at the research.

Student performance trends: local metrics improved, sometimes substantially, but gains on federal tests were unremarkable.

On certain key indicators, New York City students appeared to make significant gains. Test scores rose on state exams. High school graduation rates jumped from 54% in 2004 to nearly 75% in 2013. College enrollment and persistence rates steadily increased, though more modestly. Chronic absenteeism ebbed slightly downward. (A number of these positive trends have continued since Bloomberg left office.)

An analysis by Kemple found that between 2003 and 2013 the city made more progress than the rest of the state across both state test and graduation rates.

But these trends don’t explain whether Bloomberg’s policies or other factors propelled the improvements. For instance, New York City schools became better funded over this time period.

Additionally, graduation rates may have been boosted by the rise of credit recovery programs or failure to fully count students who dropped out.

Progress on the federal test, NAEP, was more limited. The city did make gains between 2003 and 2013, but they were generally similar to the nation as a whole and smaller than in a number of other cities; test score disparities by race didn’t change much. Unlike state exams, the NAEP is low stakes — meaning schools were not under pressure to increase scores — and thus the results may be more reliable.

Again, though, researchers warn against judging specific policies (or even a set of policies) based on these trends, meaning firm conclusions can’t be drawn.

New York City charter schools did better on state tests.

Bloomberg was a big proponent of school choice and fostered the expansion of charter schools, which now educate about 10% of the city’s public school students.

These schools, particularly their performance on state exams, have been widely studied. A number of papers show that students who attend charter schools in New York City outscore those in district schools, even accounting for demographic differences. This is also true of several specific networks that have been studied.

Other research has examined common critiques of New York City’s charters — supporting some, while debunking others. Charters tend to have higher suspension rates, serve fewer English-language learners and students with disabilities, and sometimes get substantial outside money. But they don’t appear to systematically push out low performing students or harm the performance of nearby district schools.

Letter grades led to higher state test scores in low-rated schools.

Issuing A-F letter grades for schools was one of the first things that Bloomberg’s successor Bill de Blasio scrapped.

But there is evidence that struggling schools improved test scores as a result of a low grade.

Two studies found that students scored higher on state tests in subsequent years if their school got a low grade (compared to similar schools that got a higher grade).

Research also found that earning an F led to increases in teacher retention rates at those schools. “This is an important counterpoint to the people who worry about the stigmatization effects of letter grades,” said Jonah Rockoff, an education researcher at Columbia University, previously told Chalkbeat.

Jennings, though, said that using test scores as the way to judge these policies is “deeply problematic” because schools were under such pressure to raise scores, potentially to the detriment of other domains.

More broadly, it’s possible that increased teaching to the test or low standards on the state exam might explain some of the city’s testing gains . And research can’t answer questions like whether there was too much focus on testing during Bloomberg’s tenure.

Grade retention did more harm than good in the long run.

A 2004 policy to hold back third grade students if they didn’t score high enough on math or reading tests was among Bloomberg’s most controversial. (He even fired two of his appointees to the city school board who planned to vote against his position.) The policy was extended to other grades over time.

A recent study examined the effects of grade retention, and the results were dramatic — but not in a good way. Middle schoolers, who were held back, were 10 percentage points more likely to drop out of high school as a result compared to similar students who were allowed to advance to the next grade. The same study found that elementary school retention didn’t affect drop-out rates. The policy was also quite costly since for many students it entailed an extra year of school.

“There was already a great deal of evidence that this was not going to be an effective policy,” said Jennings. “They implemented it anyway.”

On the other hand, there is some evidence that students benefited from the summer classes that came with the possibility of retention.

Closing high schools helped future students, but middle school closures didn’t do much…

A study of Bloomberg’s highly controversial high school closure policy found that the move did not help or harm students who were already attending those schools as they were phased out. But the closures did benefit future students who would have otherwise attended those high school. Students’ odds of graduating high school jumped substantially as a result, going from 40% to 55%.

“The kids who no longer had those schools on their list of options, they benefited pretty substantially,” said Kemple, who co-authored the study.

Research on closures of city middle schools, on the other hand, found little clear effects on the average student one way or the other.

… Meanwhile, small schools helped students in the long run.

What explains the benefits of high school closures? Almost certainly, one factor was the creation of new small schools that many students from closed schools ended up attending. Several studies have found that those schools did well. One recent paper showed that students who won a lottery to attend one of those schools were nearly 10 percentage points more likely to graduate high school and 4 points more likely to persist in college through four years.

Other research found that as small schools expanded, other New York City high schools also seemed to improve.

“Kids are more likely to graduate now and [from] these small schools in particular,” said Jennings. “I think that that was a very successful reform.” But she also pointed to her own research showing that certain small schools attempted to screen out or push out students who would hurt their ratings.

There’s more school choice, but persistent segregation.

Bloomberg also put in a place an extensive and complex high school choice system, using a Nobel Prize winning algorithm to determine which students get their top choices. He created new selective high schools which students must test into. There’s much more choice generally in New York City schools as a result of Bloomberg-era changes.

But it’s not entirely clear the overall effect of this proliferation of choice. What is clear is that New York City schools are currently highly segregated across many dimensions — including students’ race and academic performance. One study found that families tend to prioritize the skills of other students as opposed to the quality of the school when choosing among schools.

Currently, New York City officials are making efforts — in fits and starts — to better integrate schools. This was generally not a priority of the Bloomberg administration.

Merit pay experiment fell flat.

It was a pioneering agreement with a teachers union that had long resisted performance pay: The United Federation of Teachers gave the green light to cash bonuses for teachers in schools that made large test score gains.

But two studies found that this experiment failed to improve results for students. If anything, this group-based merit pay led to somewhat lower test scores (though it’s not clear why). Schools generally awarded the bonuses equally to all teachers, which some suggested explained the failure of the program.

A number of other policies have been studied, with mixed results:

- A touted computer-based math program known as School of One did not lead to clear test score improvements.

- School suspensions rapidly increased under Bloomberg, and research found that suspended students suffered as a result. Late in his tenure, suspensions began to decline as a result of policy changes, and this seemed to benefit students, according to a recent study.

- Stop-and-frisk — a signature and controversial policing practice that Bloomberg expanded — spilled over into public schools. Black middle school students were more likely to drop out of high school and less likely to enroll in college, research has found.

- Tightening of teacher tenure rules led to an increase in novice teachers deemed less effective to leave New York City schools.

- A teacher mentoring program that the city adopted as a result of state law increased the odds that new teachers would complete their first year.

- Providing principals with teachers’ value-added scores resulted in higher turnover rates among teachers with lower scores.

- Between 2000 and 2005, high-poverty New York City schools were staffed by more qualified teachers as measured by their years of experience and SAT scores. This may have been due to pay raises, limiting uncertified teachers, and expanding alternative certification like the Teaching Fellows.

- The principal training program known as the Leadership Academy produced principals who performed similarly as other new principals.