Reginald Williams was set to retire as principal of a Memphis charter school at the end of the school year. Instead, he was fired just days into the new school year, shortly after state test results showed the school’s scores had plummeted.

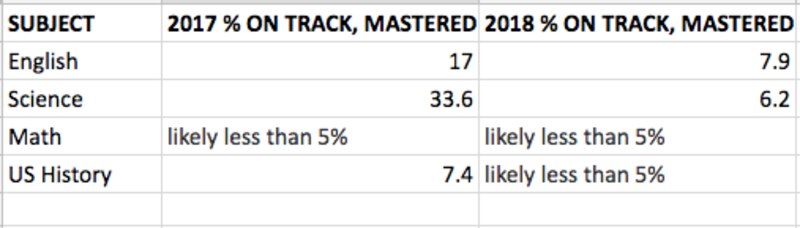

Memphis Academy of Health Sciences High School, one of the city’s first charters, had within a single year dropped from the second-highest rating on student growth to a level 1, the lowest.

School leaders who do not move the needle for academics are frequently fired, especially as a growing body of research confirms principals play a key role in student achievement. But after major technical glitches interrupted computerized testing for tens of thousands of students this spring, state lawmakers sprung into action. They passed two wide-ranging laws designed to protect teachers, students, and schools from test results that might not be reliable.

Until now, no public challenge has emerged to see how far the legislation extends — and whether or not principals are covered under it.

“You would think, though, if it’s a flawed test, that would be given consideration,” said Antonio Parkinson, a state representative whose district includes the school. “I think I would stop short of telling schools if they can move their folks around. But I would hope they would give the same consideration we gave them.”

Corey Johnson, the charter network’s executive director, told Chalkbeat he and Williams, who had served for four years as the school’s principal, had come to a “mutual agreement” about moving up the timeline for Williams’ retirement. However, emails between Johnson and the board’s president, Michael Dexter, explicitly tie Williams’ departure to poor 2018 results on the state test known as TNReady. (Chalkbeat obtained the emails through a public records request.)

“Instead of waiting until the year end, I believe it is critical to make this move now in order to show the community good faith that MAHS will moving to improve itself educational [sic],” Johnson said in the email. “It is difficult to promote high-quality education with a health science focus with the scores suggesting our school is a Level One.”

When school parents learned of Williams’ departure, many of them, together with community supporters of the former principal, overwhelmed a board meeting last month to demand answers that were not given.

When Chalkbeat asked how the state law on 2018 scores influenced his decision to fire Williams, Johnson declined to talk about the network’s former employee. He also declined to say why his reasoning was not made public to parents at the board meeting.

“MAHS, since its inception in 2003, maintains that it is our mission to cement a high-quality educational experience by providing a continuous, health science-focused curriculum,” Johnson wrote in an email to Chalkbeat. “Any changes in course in respect to that work, our faculty or administration are all made with that mission in mind.”

Williams attributed the large drop in scores to late delivery of laptops for students to practice on and a lack of motivation from students once they learned the scores would not count — a common observation among educators. When test scores came out this summer, Williams said he tried to work with Johnson on a plan to bounce back, but did not hear from him until he was fired on Aug. 10.

“I felt very strongly that’s the reason he was releasing me, but I couldn’t prove it,” he said. “I have a history of turning around programs.”

A spokeswoman for the state education department deferred questions about the legislation’s reach to local school board attorneys, though at least one state resource on interpreting the law said principals could void their evaluations based on the state law.

Shelby County Schools’ board’s attorney, Herman Morris, did not respond to several requests for comment. A district spokeswoman, meanwhile, told Chalkbeat to “speak with an attorney who is not affiliated with the charter school or the school district to answer your legal questions.”

The first year Williams was at the high school in North Memphis, the school earned the state’s highest score on student improvement. The following year it dipped, but mostly recovered before this year’s second drop.

Parkinson, the state lawmaker, said Williams’ situation is a gray area in the law. For school staff, only teachers were specifically mentioned:

For the 2017-2018 school year, [local education agencies] shall not base employment termination and compensation decisions for teachers on data generated by statewide assessments administered in the 2017-2018 school year

G.A. Hardaway, a state representative who helped establish Memphis Academy in 2003 as part of the 100 Black Men of Memphis, said he hadn’t given much thought to how the scores would impact principals.

“The goal was to make sure that everyone was held harmless from those corrupt scores and corrupt process,” he said.

At least one group is insisting that principals should be protected under the law. The legal experts at Tennessee Education Association, the state’s largest teacher group, said principals are included in the definition of “teacher” in the state law.

Back at Memphis Academy, the fallout has many parents on edge. Several of them said they are actively looking for another school for their children in light of Williams’ departure and the board’s refusal to answer questions about it.

School leaders also fired ACT prep teacher Patricia Ange, an outspoken supporter of Williams, who spoke during the board meeting. Ange said she still does not have paperwork detailing why she was fired.

De’Licia Jones, a parent who has sent her children to Memphis Academy since 2013, said the whole atmosphere has changed at the school since Williams left. Several other teachers have quit, she and other members of the school community said, and it’s impacting the students.

“Before, they would be sick and still want to go to school. They were excited,” Jones said of her children. “Now he gets to a point where he doesn’t want to go to school.”