When reviewing midyear test results for Believe Memphis Academy’s students, school leaders saw something rare in the era of virtual learning: Students on average scored 10% higher in math compared to last year. Nationally, students are scoring lower in math this year after historic disruptions to education because of the pandemic.

The small charter school in North Memphis enrolls about 330 students and opened under Shelby County Schools in 2018. Shelby County Schools did note unusual increases in test scores among students in kindergarten, first, and second grade districtwide, and assumed parents of virtual learners at home were helping their children on the online tests.

But the charter school’s students are in fourth through seventh grade, and skewed data has not been common for that age group during virtual learning. School leaders did not find any discrepancies that could explain the increase in math skills.

They have instead attributed the improvement to having more staff to support students and teachers in virtual learning, including six people dedicated to resolving technology issues and connecting families to resources. That way, teachers can solely focus on instruction.

“Not all is lost because of the pandemic. There’s still bright spots happening,” said Danny Song, head of the school. “Our children are still as resilient as they’ve ever been. As a school, we’re leaning into the things we know that, frankly, our children needed and deserved pre-pandemic.”

Believe Memphis has raised about $1 million, or about a third of its budget, from private donations, grants, and business sponsorships to pay for these extra positions. And even before federal relief money was available for schools, Jason Baker, the school’s director of development and marketing, secured $75,000 in individual and corporate donations to purchase more than 200 laptops for students last spring.

“There’s just a very intimate and very direct connection between the money that we’re raising and being able to have stories like this to tell,” Baker said.

Believe Memphis leaders say more money is desperately needed, and, if spent wisely, can lead to future academic gains.

Shelby County Schools Superintendent Joris Ray presented a similar argument in his proposal Friday to hire hundreds of teacher assistants to reduce the adult-to-student ratio in kindergarten through second grade classrooms from 1:25 to 1:13. He plans to use federal relief money — Shelby County Schools will receive $503 million — because the district has long asserted, even in court, that Tennessee does not provide enough money to educate students adequately. The assistants would help with restroom breaks, lunch duties, discipline issues, and reading tutoring.

“We want our teachers to just do what? Teach,” Ray told a crowd of about 150 guests during his annual State of the District address Friday morning. “I know the plight of our teachers. This 1-to-13 ratio is a game-changer.”

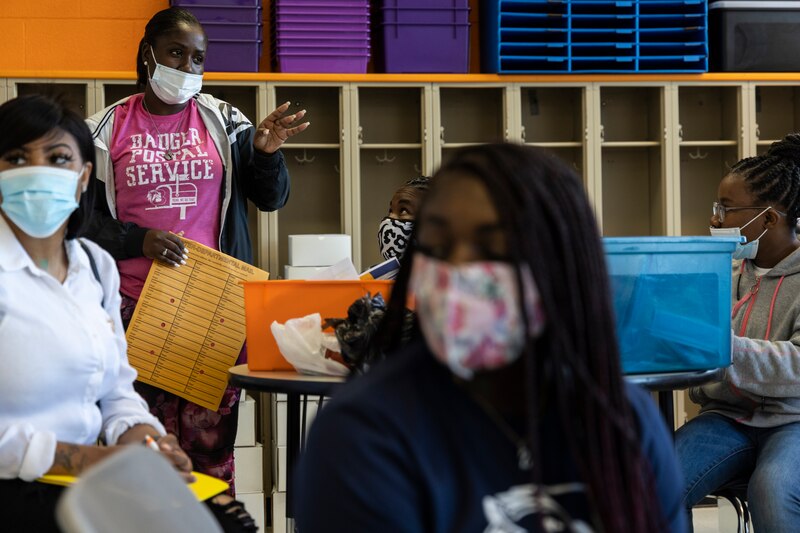

At Believe Memphis, the extra staff helped teachers have more time to teach. Teachers have also been meeting more often to dig into testing data for each student and tailoring strategies to help them individually, which allows them to stay connected in an otherwise lonely time.

Because of the extra staff, Addie Willis, the school’s literacy intervention coordinator, said what used to take up to 25 minutes to get students on a video call and settled now takes five minutes.

“It’s been great for the amount of content we can get through in that period of time,” she said.

To give real-time feedback on classwork and assignments, the school uses software that allows teachers like Willis to see exactly what students see on their laptop screens without waiting for students to grant screen-sharing access.

That saved her time during a recent class when a student misunderstood where the class was in the lesson. The student was on the third page in a presentation instead of the third math problem as instructed. Willis was able to toggle to his screen quickly and notice the mistake, as if she were in the same room with him and could look over his shoulder.

Each homeroom has someone dedicated to checking on students who don’t log in to video calls for class or who may be distracted or frustrated during class. Some students just need a reminder to log on, while others may be having trouble with internet connections or software. Still others may be having a family emergency and school staff may help connect them to resources, such as mental health counseling, meal delivery, or utilities assistance.

Tarus Williamson said her son, Nathaniel Bradshaw, a seventh grader at Believe Memphis, hasn’t missed a beat during virtual learning. When Nathaniel isn’t paying attention to his online classes, it’s common for Williamson to get a text or a call from a staff member to help redirect him.

Williamson lives with her adult daughter who works while Williamson watches Nathaniel and her grandson, who attends second grade at another school. Since the pandemic started, Williamson said the Believe Memphis staff have been proactive in reaching out to her to see what she needs.

Back injuries have forced her to rely on a walker, and she doesn’t have a car, so Believe Memphis staff deliver Nathaniel’s weekly supply of school breakfast and lunch every Tuesday. When the school closed last spring, a staff member signed her up for the internet over the phone rather than just sending a link to free Wi-Fi services.

“That nurturing type of feel is required for these babies,” Williamson said. “They’re touching the children virtually.”