Mayor Bill de Blasio has staked much of his education agenda on improving high-need schools by flooding them with hundreds of millions of dollars worth of additional social services and resources, efforts that have so far posted disappointing results.

But research released Tuesday focused on the city’s “community schools” program — providing wrap-around services, such as additional counselors and longer school days — offers new evidence that the mayor’s approach is bearing some fruit.

The study, conducted by the Rand Corp. and commissioned by the city, found the program has led to improvements in attendance, graduation rates, math scores, and the rate at which students advance to the next grade level.

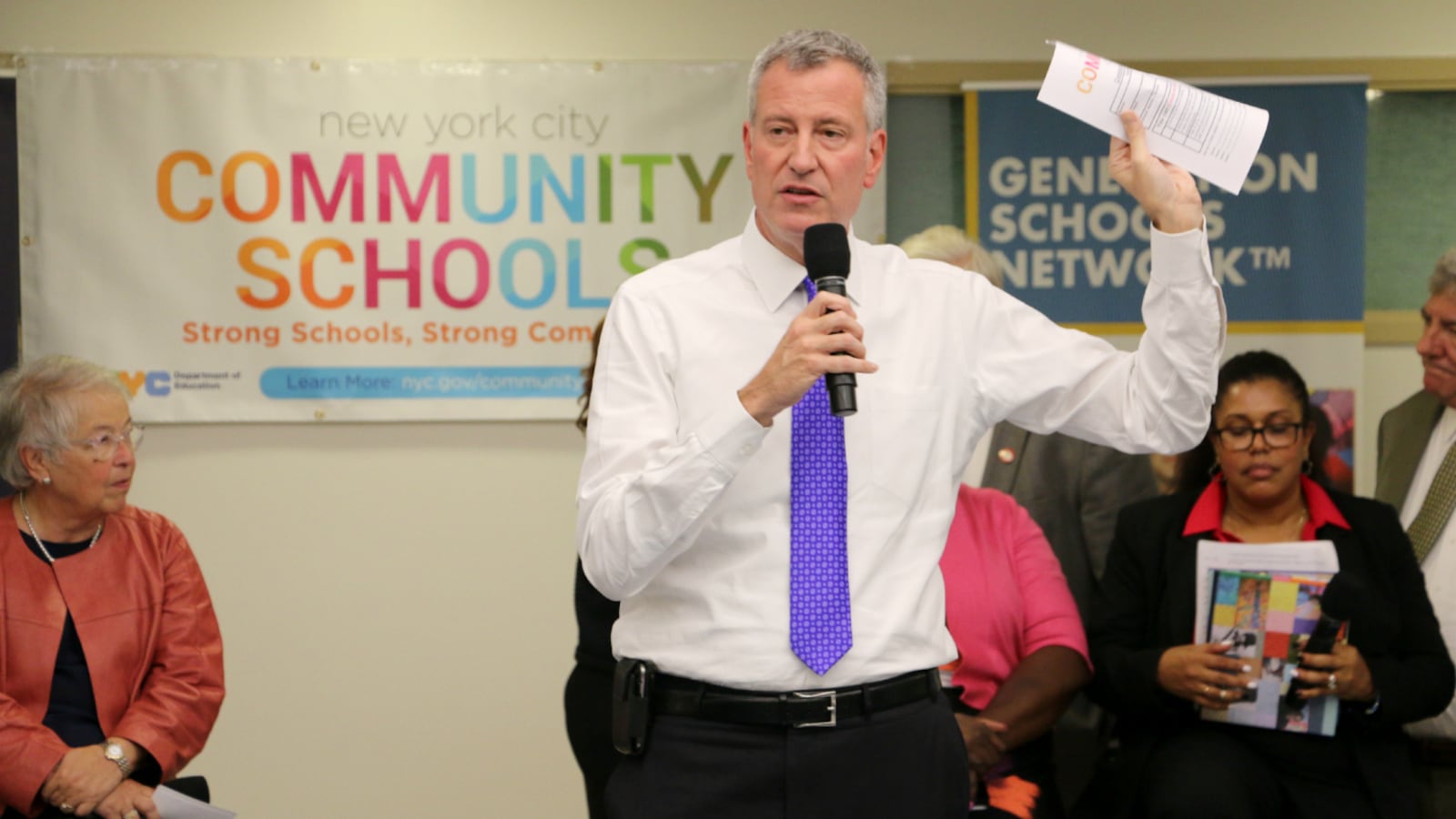

“The verdict is in: community schools work,” de Blasio trumpeted during a press conference Tuesday at Brooklyn’s P.S. 67.

The findings are good news for a mayor whose signature $773 million school improvement program, which deployed many of the same approaches as the community schools initiative, was found to have had few positive effects and was ultimately disbanded last school year.

With 267 community schools, New York City boasts the largest network of such schools in the country. Community school supporters argue students can’t learn if their basic needs are unmet, which means the schools often offer services such as washing machines, food pantries, and direct outreach to help families get their children to school. Past studies have yielded mixed results from other community school programs, but the latest findings could prompt other districts to adopt the model.

“To overcome the cycle of poverty and other obstacles it is important to support the whole family,” Carmen Fariña, who ran the education department when the community school initiative launched, wrote in an email. “Real reform is finding good strategies and staying the course. No magic wand.”

Still, the study includes some findings that are less encouraging. The community schools program did not improve middle or elementary school reading scores, as measured by state tests, though it did lead to a statistically significant improvement in math scores across years. And while the program kept disciplinary incidents from rising in elementary and middle schools, it had no effect on that measure among high schools.

“Patience is important; whole school reforms take time to move the needle, academic achievement in particular,” said William Johnston, one of the report’s authors. “I see this as a positive story that community schools have the potential to reap benefits for students in disadvantaged communities.”

The study attempts to isolate the effect of the community schools program by using student-level data to compare 113 of the city’s community schools with 399 other city schools that had similar demographics and levels of student achievement, but which did not receive a slew of new resources. Differences in outcomes between the two groups of schools could then be linked to the community schools program. The study looked at outcomes during the three school years after it was launched in 2014.

Every community school uses a slightly different combination of resources, but they typically create an hour of extra learning time, conduct outreach to families to boost attendance, and receive an extra staff member to help coordinate the program.

The schools also all partner with nonprofit organizations that offer a range of services, such as mental health counseling, vision screenings, or dental checkups. The program costs roughly $200 million a year; the city’s Independent Budget Office found that a majority of the money supported academics rather than social services.

Those efforts helped prompt students to show up to school more often. Before the program took effect, about 40% of students at community middle and elementary schools were chronically absent, meaning they missed at least 10% of the school year. By 2018, that number had dropped to roughly 32%. In contrast, the comparison schools outside the program only improved chronic absenteeism by about one percentage point.

Among elementary and middle schools in the community program, disciplinary incidents stayed relatively flat, with nearly 30 incidents per 100 students a year. That bucked the trend among schools that did not receive extra help, which saw an increase of roughly 7 incidents to 37 per 100 students over the same period.

The findings also include something of a mystery: Most of the community schools included in the study were also part of de Blasio’s Renewal turnaround program. The Renewal schools included in the community schools study appeared to drive much of the gains in measures including graduation rates and chronic absenteeism. That is in tension with a prior Rand report that has generally found the program failed to significantly improve graduation rates and test scores.

Johnston, who was an author on both reports, said there isn’t a “definitive answer” about why Renewal schools appeared to perform so well. But he noted that the Renewal study included one less year of data and used a different statistical method to measure its impact.

The study includes some important limitations: Because community schools were not randomly assigned, it’s possible that there are outside factors that the researchers couldn’t measure that affected their results. It’s also unclear whether a similar set of interventions would have the same effect in other school districts; research that tries to pinpoint why certain community schools are effective has proved inconclusive.

Jennifer Jennings, a Princeton University researcher who reviewed the report at Chalkbeat’s request, said the approach is rigorous and that the findings are promising.

Still, she noted that the study doesn’t attempt to answer questions about whether an investment in community schools is better or worse than other initiatives, such as class size reductions or efforts to attract more effective teachers.

“The question is really: Did it work better than other things that cost similar amounts of money or with fewer public dollars?” she said. “If I was the superintendent of [Los Angeles schools], would I take this evidence and go forward with it? I think I’d want the answers to a lot more questions before doing that given the costs.”

Chalkbeat submitted a public records request in November for the study under the state’s Freedom of Information Law and was told it wouldn’t be ready until February. But the city ended up giving an advanced copy to the Washington Post, which published a story on the report Tuesday morning.

“Once the report was determined to be publicly available, there should have been no further delay in disclosure” to Chalkbeat, wrote Kristin O’Neill, the assistant director of the state’s Committee on Open Government.

Freddi Goldstein, a mayoral spokesperson, indicated the report should have been disclosed through the open records process.

“If it’s how you’ve described, that shouldn’t have happened and I’ll make sure it doesn’t again,” she tweeted.